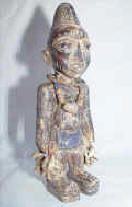

SALAMPASU

(ASALAMPASU,

BASALAMPASU, MPASU)

Democratic Republic

of the Congo

The

60,000 Salampasu people live east of the Kasai River, on the frontier

between the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Angola. Their name is said

to mean “hunters of locusts”, but they were widely viewed with terror by

adjacent groups. They maintain strong commercial and cultural relations with

their southern neighbors, the Chokwe and the Lunda to whom they pay tribute.

The Salampasu are homogeneous people governed by territorial chiefs, who

supervise village chiefs. Their hierarchical power structure is

counterbalanced by a warriors' society. A people with a reputation as

fearless warriors, the Salampasu have retained the custom of a rough and

primitive life. Warring and hunting are privileged occupations, but the

women do some farming.

Salampasu masks were integral part of the warriors’ society whose primary

task was to protect this small enclave against invasions by outside

kingdoms. Boys were initiated into the warriors’ society through a

circumcision camp, and then rose through its ranks by gaining access to a

hierarchy of masks. Earning the right to wear a mask involved performing

specific deeds and large payments of livestock, drink and other material

goods. Once a man ‘owned’ the mask, other ‘owners’ taught this new member

particular esoteric knowledge associated with it. The Salampasu use masks

made from wood, crocheted raffia, and wood covered with sheets of copper.

Famous Salampasu masks made for initiation purposes are characterized by a

bulging forehead, slanted eyes, a triangular nose and a rectangular mouth

displaying intimidating set of teeth. The heads are often covered with

bamboo or raffia or rattan-like decorations. Presented in a progressive

order to future initiates, they symbolize the three levels of the society:

hunters, warriors, and the chief. Certain masks provoke such terror that

women and children flee the village when they hear the mask's name

pronounced for fear they will die on the spot. Wooden masks covered or not

covered with copper sheets are worn by members of the ibuku warrior

association who have killed in battle. The masks made of plaited raffia

fiber are used by the idangani association. Throughout the southern

savannah region copper was a prerogative of leadership, used to legitimize a

person’s or a group’s control of the majority of the people. Possessing many

masks indicated not only wealth but also knowledge. Filing teeth making part

of many wooden masks was part of the initiation process for both boys and

girls designed to demonstrate the novices’ strength and discipline.

Salampasu masquerades were held in wooden enclosures decorated with

anthropomorphic figures carved in relief. The costume, composed of animal

skins, feathers, and fibers, is as important as the mask itself. It has been

sacralized, and the spirit dwells within it. Masks are still being danced as

part of male circumcision ceremonies. |

|

Ceremonial mask. A warrior people

comprising 60,000 individuals, the Salampasu live in Shaba province between

the rivers Lulua and Lueta, tributaries of the Kasai River. Their name is

said to mean “hunters of locusts”, but they were widely viewed with terror

by adjacent groups. They have retained the customs of a rough and primitive

life. The Salampasu live mostly from hunting, but the women do some farming.

The masks, regardless of their material composition, are worn in the

initiation rites of men’s associations, on occasion of bereavement or

enthronement, as well as to pay homage to headhunters. The costume

accompanying this type of mask consists of a fiber net adapted to the body,

and a skirt of fiber or animal fur. The wearer holds antelope horns or a

two-edged sword. Salampasu masquerades were held in wooden enclosures

decorated with anthropomorphic figures carved in relief.

Material: wood, copper sheets,

vegetable fiber

Size: 15" x 10" x 9" |

SENUFO

(SENOUFO, SIENA, SIENNA)

Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire, Ghana and Mali

The Senufo number 1,000,000 to 1,500,000 and

live in Côte d'Ivoire, Ghana, Burkina Faso, and the extreme south of Mali.

They live principally off the fruits of agriculture and occasionally

hunting. Senufo agriculture is typical of the region, including

millet, sorghum, maize, rice, and yams. They also grow bananas, manioc, and

a host of other crops that have been borrowed from cultures throughout the

world. Small farm animals such as sheep, goats, chickens, guinea fowl, and

dogs are raised. Minimal amounts of hunting and fishing also contribute to

the local economy. Labor is divided between farmers and skilled artisans,

and while it was once thought that these segments of society did not

intermarry, In addition to a belief in a creator deity,

ancestors and nature spirits, a central concept in Senufo religion is a

female ancestral spirit called “ancient mother” or “ancient woman,” the

sacred guiding spirit of each poro society. All adult men belong to

the poro society, which maintains the continuity of religious and

historical traditions, especially through the cult of the ancestors. The

poro is the pillar of communal life. Responsible for initiation and

training of the young boys, it is aimed at shaping an accomplished, social

man who is integrated to the collective; it aids his entry into public

responsibilities. A woman’s association, the sandogo, in charge of

divination, is responsible for contact with the bush spirit who might be

bothered by the activities of the hunt, farming, or of artisans.

The

Senufo produce a rich variety of sculptures, mainly associated with the

poro society. The sculptors and metal smiths, endogamous groups

responsible for making the cult objects live on their own in a separate part

of the village. The attitude shown toward them by other Senufo is a mixture

of fear and respect, owing to their privileged relationship with the natural

forces that they are capable of channeling in a sculpture. During

initiations, headpieces are worn that have a flat, vertical, round or

rectangular board on top decorated with paint or pierced work. Many wood

carvings of male figures depict these headpieces, sometimes on rhythm

pounders used by young initiates, who beat the earth to call upon the

ancestors to take part in the ceremony and purify the earth. The

carvers also produce ritual female statues, including mother-and-child

figures, as well as statuettes depicting bush spirits and supernatural

beings and equestrian figures. Large statues representing hornbills

(often seen also on masks) and used in the lo society as symbols of

fertility are the standing birds called porpianong. Figures of the

hornbill are used in initiation, and groups of birds on a pole are trophies

for the best farmer. Figures of male and female twins and of horsemen are

used in divination. These represent the spirit familiars enabling the

divination process. Shrine doors and drums are carved in relief, and small

figures and ritual rings are cast in bronze.

Several types

of mask are used depending upon the occasion. The kpelie, a human

face with projections all around, is said to remind initiates of human

imperfection. Danced by men, these masks perform as female characters.

Animal-head masks usually combine characteristics of several

creatures--hyena, warthog, and antelope. A type of animal mask called

waniugo has a cup for a magical substance on top; these masks blow

sparks from their muzzles in a nighttime ritual protecting the village from

sorcerers. Among the Naffara group of the Senufo, masks of similar form but

with an interior cavity too small for a human head are carried on the top

corner of a rectangular, tent like costume called kagba. This mask is

the symbol of the Lo, which only initiates may see. In the Korhogo

region, deguele masks appear in pairs at funerals. They are of plain

helmet shapes topped with figures whose bodies are carved to resemble a pile

of rings. |

|

Chair Chair

Unlike stools, Chairs in Africa are thought to have

been influenced by European models. However, each group incorporates its own

styles into the chair design. Used by elders for seating.

Materia: wood

Size: 40" x 23" x 22" |

Door. . The Senufo

produce a rich variety of sculptures, mainly associated with the Poro

society, to which adult men belong and which maintains the continuity of

religious and historical traditions, especially through the cult of the

ancestors. Senufo carved doors decorate initiation training houses and

household protective shrines. Their motifs are associated with esoteric

knowledge of divination, bush spirits, and other sources of power, which are

acquired secretly in order to combat forces that threaten communal

well-being.

Material: wood.

Size: 68" x 19" x 2" |

Material: wood

Size: 38" x 19" x 9" |

Female rhythm pounder (deble). The Senufo, about 1

million in number, live mostly in Cote d’Ivoire, but also in Ghana, Burkina

Faso and the extreme south of Mali. They are concentrated in villages

composed of 800 to 1200 inhabitants, broken up into units of matrilineal

lineage descending from a common ancestor. Endogamy within the lineage was

forbidden and punishable by death.

The Senufo produce a rich variety of sculptures, mainly associated with the

Poro society, to which adult men belong and which maintains the

continuity of religious and historical traditions, especially through the

cult of the ancestors. They have a vital masquerading tradition associated

with various male societies, including Poro. Pounders

made from a single piece of wood on a circular base are used to provide the

rhythm for a dance in the Lo society. Such implements are also used

to invoke the spirits of the ancestors, especially at agricultural

ceremonies. Such figures are pounded against the ground in time to the

music.

Material: wood

Size: 63" x 12" x 12" |

Kpelie initiation mask.

The Senufo produce a rich variety of

sculptures, mainly associated with the Poro society, to which adult

men belong and which maintains the continuity of religious and historical

traditions, especially through the cult of the ancestors. The kpelie

is an ancestor mask, which is used at the ceremony of the lo

society which governed the social life of the tribe. Although the occasions on which it is used may differ, it always

represents the face of a female ancestor with formerly common tatooes,

closely connected to the society’s origin. According to one source, the

kpelie is said to remind initiates of human imperfection. Worn at a

funeral, the kpelie masks serve to compel the spirit of the deceased

to leave the house.

Material:

wood

Size:

16" x 10" x 4" |

|

40" x 23" x 22" |

68" x 19" x 2" |

38" x 19" x 9" |

63" x 12" x 12" |

16" x 10" x 4" |

Wanyugo helmet mask. In

the southern Senufo region a society known as wabele battles sorcery

or negative influences and harmful spirits that appear in form of wild

animals or monsters and threaten people in times of crisis or vulnerability.

The society’s most important paraphernalia are wanyugo masks, which

are considered especially dangerous, even being said to occasionally breathe

fire or emit swarms of bees. Design features recalling various wild animals

underscore the mask’s aggressiveness: powerful jaws with sharp teeth

represent a crocodile’s or hyena’s snout. The mask has extraordinary powers,

which came into play in the context of a ceremony.

Material: wood

Size: 12" x 9" x 19 |

Equestrian figure (Syonfolo).

Most Senufo diviners receive their training as members of Sandogo, a

powerful women’s organization that unites female leaders from a community’s

various households. Senufo wood and copper-alloy figures that depict

equestrian warriors, such as this one, are not essential components of a

Sando (member of Sandogo) diviner’ kit. Instead, they constitute

artistically accomplished tributes to the professional success of the

diviners who commissioned them. The dazzling beauty of these prestige

pieces, amplifies the efficacy of the diviner’s basic set of implements by

enhancing her ability to attract the interest and favor. Since only the most

successful diviners can afford to engage the sculptors to create such works,

their ownership and display in turn indicate to the community at large the

diviner’s attainment of an exceptional level of professional competence.

Material: wood

Size: 35" x 7" x 8" |

Stools 13" x 16" x 16" each |

11" x 23" x 11" |

11" x 19" x 16" and

22" x 11" x 15" |

|

SONGYE (BASONGE, BAYEMBE, SONGE, SONGHAY,

WASONGA)

Democratic Republic of the Congo

During the 16th century, the Songye migrated from the Shaba area, which is

now the southern part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Their history

is closely linked to the Luba's, to whom the Songye are related through

common ancestors. Having waged war against one another for a long time, the

Songye and Luba later formed an alliance to fight the Arabs. They settled on

the left bank of the Lualaba River, on a savanna and forest-covered plateau.

Divided into many subgroups, the 150,000 Songye people are governed by a

central chief assisted by innumerable secret societies.

The

Songye traditionally relied mostly on farming and hunting for subsistence.

Because the rivers were associated with the spirits of deceased chiefs who

were often buried in them, fishing was not practiced except in times of

great need. The artistic wares of the Songye, including pottery made by

women and weaving and metalworking done by men, were traded extensively with

their neighbors.

The Songye created a sculptural style of intense dynamism and vitality. The

works of Songye craftsmen are often used within the secret societies during

various ceremonies. They produced a large number of figures belonging to the

fetishist, who manipulates them during the rituals of the full moon. Songye

fetish figures vary in size from 4” to 60”. They are usually male and stand

on a base. Strips of metal, nails or other paraphernalia are sometimes

applied over the face, which counteract evil spirits and aggressors and

channel lightings against them. The top of the head and the abdomen are

usually hollowed to allow insertion of fetish material, called boanga.

These figures adopt a hieratic posture, the hands placed on a pointed

abdomen; on top of the head they have a horn or feathers reinforcing a

disquieting appearance. The fetishist would make the boanga with

magic ingredients, which he crumbled and mixed, thus obtaining a paste that

was kept in an antelope horn hung from the roof of the house. The magic

ingredients consist of a wide variety of animal, vegetal, mineral and human

substances that activate and bring into play benevolent ancestral spirits.

The face is often covered with nails, a reminder of smallpox. The style of

Songye fetishes, carved from wood or horn and decorated with shells, is not

as realistic as the classic Luba style, and their integration of

non-naturalistic, more geometric forms is impressive. The figures are used

to ensure their success, fertility, and wealth and to protect people against

hostile forces as lightning, as well as against diseases such as smallpox,

very common in that region. While smaller figures of this type were kept and

consulted by individuals, larger ones were responsible for ensuring the

welfare of an entire community.

In the Songye language, a mask is a kifwebe:

this term has been given to masks representing spirits and characterized by

striations. Depending on the region, it may be dark with white strips, or

the reverse. The kifwebe masks embodied supernatural forces. The

kifwebe society used them to ward off disaster or any threat. The masks,

supplemented by a woven costume and a long beard of raffia bast, dance at

various ceremonies. They are worn by men who act as police at the behest of

a ruler, or to intimidate the enemy. It can be either masculine, if carved

with a central crest, or feminine if displaying a plain coiffure. The size

of the crest determines the magic power of the mask. Mask, colors, and

costume all have symbolic meaning. The dancer who wears the male mask will

display aggressive and uncontrolled behavior with the aim of encouraging

social conformity, whereas the dancer who wears the female mask display more

gentle and controlled movements and is assumed to be associated with

reproduction ceremonies. The use of white on the mask symbolizes positive

concepts such as purity and peace, the moon and light. Red is associated

with blood and fire, courage and fortitude, but also with danger and evil.

Female masks essentially reflect positive forces and appear principally in

dances held at night, such as during lunar ceremonies and at the investiture

or death of a ruler. The mask had also the capacity to heal by means of the

supernatural force it was supposed to incorporate. The ritual of exorcism

consisted of holding the sick man’s mask while a magician acted as if he

were casting it into the fire. Kifwebe mask representations also

appear on other objects belonging to the kifwebe society – grooved

shields, for example, are adorned with a central mask. Buffalo masks with a

brown patina that have no stripes were used in hunting rituals.

The Songye also produce prestige stools,

ceremonial axes, made of iron and copper and decorated with interlaced

patterns, neckrests, bracelets and copper adzes.

|

Songye (Basonge, Bayembe, Songe, Wasonga),

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Fetish. The 150,000

Songye settled in the southeast of the country have a strong interest in

magic, which affects many aspects of their lives. The Songye carvers excel

in the production of fetishes and expressionistic masks.

Songye fetish figures vary in size from 4”

to 60”. While smaller figures of

this type were kept and consulted by individuals, larger ones were

responsible for ensuring the welfare of an entire community.

These figures adopt a hieratic posture, the

hands placed on the abdomen; on top of the head they may have a horn

reinforcing a disquieting appearance.

The top of the head and the abdomen are

usually hollowed to allow insertion of fetish material, called boanga.

The fetishist would make the boanga with magic ingredients, which he

crumbled and mixed, thus obtaining a paste that was kept in an antelope horn

hung from the roof of the house. The magic ingredients consist of a wide

variety of animal, vegetal, mineral and human substances that activate and

bring into play benevolent ancestral spirits. The fetishes

are intended to ward off evil, to preserve the tribe or the family from

hostile powers, sorcerers or evil spirits, and to aid fertility.

Material: wood, shells, rafia |

Songye (Basonge, Bayembe, Songe, Wasonga),

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Chief’s staff. Many of ancient Songye

traditions have survived, among them the use of staffs as emblems of

leadership.

Chief’s staffs were both prestige items and receptacles for sacral power.

Sanctified by ritual specialists, they took on supernatural qualities and

were said to have healing power. A Songye staff is like an enlarged detail

of a map, for a staff tells the story of an individual family, lineage, or

chiefdom. The map is read vertically, from top to bottom. As one progresses

down the staff, it is as if one were journeying across the Songye landscape,

through the uninhabited savanna represented by the plain, unadorned staff.

Material: wood |

Songye

Game Board Songye

Game Board |

Songye (Basonge, Bayembe, Songe, Wasonga),

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Protective figurine.

The 150,000 Songye live in the southeast of the country. Culturally and

linguistically they are related to the Luba. Divided into numerous

sub-groups, the Songye are governed by a central chief whose role demands

that he obey special restrictive laws such as not showing grief, not

drinking in public and not shaking hands with men. The Songye have a strong

interest in magic, which affects many aspects of their lives. The Songye

create protective figures in a range of sizes. They are thought of as

protectors against physical ailments and aggression from outside and are

aides related to healing and therapy. They also promote fertility. The

present figurine is of this type.

Material: wood |

Kifwebe

male mask. In the Songye

language, a mask is a kifwebe;

this term has been given to masks representing spirits. The kifwebe

society used them to ward off disaster or any threat. The mask had also the

capacity to heal by means of the supernatural force it was supposed to

incorporate. The masks, supplemented by a woven costume and a long beard of

raffia bast, dance at various ceremonies. Mask, colors, and costume all have

symbolic meaning. The use of white on the mask symbolizes positive concepts

such as purity and peace, the moon and light. Red is associated with blood

and fire, courage and fortitude, but also with danger and evil. The dancer

who wears the male mask will display aggressive and uncontrolled behavior

with the aim of encouraging social conformity, whereas the dancer who wears the

female mask display more gentle and controlled movements and is assumed to

be associated with reproduction ceremonies.

The female mask distinguishes from the male

one by the absence of a crest on top of the head. The

wave-like pattern of broad stripes in contrasting color may provide a hint

as to the region of origin -- perhaps that of the eastern Songye.

Material: wood

|

|

38" x 13" x 13 |

35" x 4" x 2" |

17" x 8" x 5" |

|

23" x 13" x 11" |

Kifwebe

male mask. In the Songye

language, a mask is a kifwebe;

this term has been given to masks representing spirits. The kifwebe

society used them to ward off disaster or any threat. The mask had also the

capacity to heal by means of the supernatural force it was supposed to

incorporate. The masks, supplemented by a woven costume and a long beard of

raffia bast, dance at various ceremonies. Mask, colors, and costume all have

symbolic meaning. The use of white on the mask symbolizes positive concepts

such as purity and peace, the moon and light. Red is associated with blood

and fire, courage and fortitude, but also with danger and evil. The dancer

who wears the male mask will display aggressive and uncontrolled behavior

with the aim of encouraging social conformity, whereas the dancer who wears the

female mask display more gentle and controlled movements and is assumed to

be associated with reproduction ceremonies.

The female mask distinguishes from the male

one by the absence of a crest on top of the head. The

wave-like pattern of broad stripes in contrasting color may provide a hint

as to the region of origin -- perhaps that of the eastern Songye. Kifwebe

male mask. In the Songye

language, a mask is a kifwebe;

this term has been given to masks representing spirits. The kifwebe

society used them to ward off disaster or any threat. The mask had also the

capacity to heal by means of the supernatural force it was supposed to

incorporate. The masks, supplemented by a woven costume and a long beard of

raffia bast, dance at various ceremonies. Mask, colors, and costume all have

symbolic meaning. The use of white on the mask symbolizes positive concepts

such as purity and peace, the moon and light. Red is associated with blood

and fire, courage and fortitude, but also with danger and evil. The dancer

who wears the male mask will display aggressive and uncontrolled behavior

with the aim of encouraging social conformity, whereas the dancer who wears the

female mask display more gentle and controlled movements and is assumed to

be associated with reproduction ceremonies.

The female mask distinguishes from the male

one by the absence of a crest on top of the head. The

wave-like pattern of broad stripes in contrasting color may provide a hint

as to the region of origin -- perhaps that of the eastern Songye.

Material: wood

Size:

44" x 22" x 9" |

SUKU

(BASUKU)

Democratic Republic

of the Congo

The

80,000 Suku people have lived in the southwestern part of the Democratic

Republic of the Congo since the 16th century. Their main economic resource

is farming. Cultivation of yams, manioc, and groundnuts is done

primarily by women. This is supplemented by the men hunting with dogs in the

surrounding forest and by the women gathering wild berries, nuts, and roots.

Occasional fishing in the Kwango River also provides some food. Although

hunting rarely provides substantial quantities of meat to the Suku diet, it

is considered an important part of male culture. Palm tree plantations

provide the Suku with palm oil, an important commodity for local and

international trade.

The

wood sculpture is a royal court art linked to the social hierarchy. The

statues that contain magic ingredients have malevolent or beneficial

functions. The medications are placed in the figure’s abdomen, which is

closed up with a resin stopper, or enclosed in small bags hung around the

neck or waist. The statue is kept in a hut that stands with in the enclosure

of the chief’s house. The Suku of the north have statues, the

mulomba: these have one hand outstretched to solicit a

gift. The sculptures wear the hairdo typical of the chiefs of the territory

and lineage. The Suku also carve figures, which are used during fertility

ceremonies and kneeling or crouching fetish figures. These are used either

as ancestor figures or as the personification of the evil spirit.

The Suku have

an initiation, the n-khanda. A special hut is built in the forest to

give shelter to the postulants during their retreat; the event ends in

circumcision, an occasion for great masked festivities including dances and

song. The masks fulfill several functions: some serve as protection against

evil forces, others ensure the fertility of the young initiate. Their role

consists in frightening the public, healing the sick, and casting spells.

The charm masks of the initiation specialist do not "dance." Their

appearance must engender terror, especially the

kakuungu,

with its swollen cheeks, massive features, and protruding chin. The Suku

also used hemba

helmet masks. These are cut from a cylinder of wood, the hairdo often

surmounted by a person or animal. These masks are supposedly an image of the

community of deceased elders, notably the chiefs of the maternal lineage.

They are used to promote success in the hunt, to heal, and to punish

criminals. They were also worn by dancers during certain initiation

ceremonies. |

|

Suku Suku |

Suku

Protective figurine Suku

Protective figurine |

Suku. Kakungu ceremonial mask. The 80,000 Suku inhabit

the Southwest of the DRC. Their main economic resources are farming and

hunt. In Suku society, boys’ coming-of-age preparation is the responsibility

of the Nkanda association. In the seclusion of lodges located outside

the village, boys between the ages of ten and fifteen years are taught the

history and traditions of their people and undergo obligatory circumcision.

They also learn the songs and dances that will be performed at their

initiation ceremonies. Several different masks are used in the Nkanda

graduation ceremonies. Kakungu is the largest of the initiation

masks. The mask appears on the day of circumcision and again when the young

man leaves the lodges to return to the village. Kakungu masks instill

in the young men obedience and respect for their elders. These masks are

also protective, threatening anyone suspected of harboring evil intentions

against the initiates. They are also called upon for the treatment of

impotence and sterility. The kakungu mask has assertive and

impressive form, with a large forehead and bulging cheeks. When not in use,

they are displayed in shrines.

Material: wood, raffia

Size: 36" x 21" x 8" with raffia |

Suku. Ceremonial Mask Suku. Ceremonial Mask

Material: wood, pigments, raffia

Size: 19" x 13" x 11 + raffia

THIS ITEM HAS BEEN SOLD (SWEDEN) |

|

Ceremonial Mask

Material: wood

Size: 24" x 10" x 12" |

Ceremonial Mask

Material: wood

Size:

27" x 13" x 10" |

TABWA

Democratic Republic of the Congo and Zambia

The Tabwa people lived under Luba domination

in small autonomous villages scattered within a territory that expanded from

the southeast of the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the northeast

of Zambia, along Lake Tanganyika. The verb "tabwa" means "to be tied up"

and refers to when these people were taken as slaves. During the 19th

century, the ivory trade brought wealth to the region and Tabwa people

gained their independence. Today, they number 200,000 and are led by

chiefs-sorcerers who rule over village chiefs and family chiefs. Their power

is counterbalanced by male societies created on Luba prototypes and by

female associations influenced by East African models. Traditionally, Tabwa

people made their living from hunting and blacksmithing; nowadays they

cultivate millet, manioc, cassava, beans, and corn, but they live

primarily off fishing and hunting, for game is plentiful. The

influence of Eastern Tanzanian neighbors on Tabwa art is seen in their use

of linear geometric decorations, while their western neighbors, the Luba,

influenced the incorporation of prestige objects into Tabwa life.

The Tabwa worshipped ancestors, whose statues were the property of the

lineage chiefs and sorcerers; these carried “medications” in their ears or

in small cavities at the top of their heads. The Tabwa also worshipped the

spirits of nature, who lived in trees and rocks. The installation of a

supreme chief is of relatively recent vintage; formerly it was the function

of the large ancestor figures to consolidate the power of the chiefs. Other

statuettes were used for divination. The Tabwa also made twin figures that

could be both dangerous and bearers of good luck. In the north of Tabwa

country, the diviner was also a sculptor; consulted after a dream, he would

create a new statue. Special attention was paid to scarifications, which

embellish the body and recall social values. On the whole surface of the

body, a recurrent motif consists of twinned isosceles triangles, the two

bases of which symbolize the duality of life. They evoke the coming of the

new moon, essential to Tabwa philosophy, whose return would be celebrated

monthly.

The

Tabwa used two types of masks: a human one, which represented woman, and

another in the form of a buffalo head, which represented man. Both would

make an appearance at the time of the fecundity ritual, celebrated for

sterile women. One also finds paddles, combs, and musical instruments with

figurines.

|

Lake Tanganyika and some part of the northeastern

Zambia. They are led by

chiefs-sorcerers who rule over village chiefs and family chiefs. Their power

is counterbalanced by male societies created on Luba prototypes and by

female associations influenced by East African models. Traditionally, Tabwa

people made their living from hunting and blacksmithing; nowadays they

cultivate millet, manioc, and corn, but they live primarily off fishing

and hunting. The Tabwa worshipped ancestors, whose statues were the property

of the lineage chiefs and sorcerers.

Tabwa lineage elders kept

small wooden images to represent and honor ancestor spirits, great healers,

and occasionally earth spirits. The figure displays elaborate scars. Such

adornment was esthetically pleasing and served as visual metaphors that

implied positive social values and the harmony of natural forces.

Material: wood

Size: 28" x 13" x 10" |

TANZANIA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

26" x 11" x 4" |

|

41" x 13" x 10" |

41" x 12" x 11" |

|

TEKE (ANZIKA, BAKONO, BATEKE, M'TEKE,TEGE,

TEO, TERE, TSIO)

Both Congo Republics and Gabon

The name of this people indicates its occupation—that is, trading—from

teke, meaning “to buy.” The Teke settled in a territory lying across

Republic of Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Gabon. During

the 15th century they were integrated into the Tio kingdom, but attained

independence in the 17th century. The basic social unit was the

family, under the authority of the mfumu, or head of the family; the

latter had the right of life and death over all family members and his

prestige grew as their number grew – hence a tendency to own many slaves to

increase one’s power and reputation. In terms of spiritual life, the

mfumu mpugu, the village chief chosen as religious leader, was the most

important personage; he kept the basket that contained the magic statuettes

and the bones of the ancestors. The Teke often chose a blacksmith as chief –

an important person in the community whose profession was passed down from

father to son. The diviner, both sorcerer and healer, was also powerful;

facilitating retributions, he would render effective the mussassi,

personal protective statuettes, and would perform divination in instances of

illness or death. The economy of the Teke is mainly based on

farming maize, millet and tobacco, but the Teke are also hunters, skilled

fishermen and traders. They believe in a supreme being, the creator of the

universe called Nzambi, whose favors can be

obtained with the help of tutelary spirits.

Teke artists carved fetish figures. Three elements are characteristic: a

variety of headdresses, the presence of fine parallel scarifications on the

cheeks, and the addition of fetish materials bonga either in an

abdominal cavity or in a body-enveloping sack from which the head and feet

protrude. Each figure has its own specific purpose not related directly to

its appearance. For example, when a figure is carved for a newborn child,

part of the placenta is placed in the stomach cavity of the figure while the

rest is buried inside the father's hut (where the family's fetish figures

are kept). The figure serves to protect the child until puberty. Figures of

identical appearance serve also for success in hunting, trading, and other

activities, each figure's purpose being known only to the owner. These

figures protect and assist the Teke and, if a fetish figure successfully

demonstrates its power, its owner may detach bonga, break it into

several pieces and insert fragments into other figures. He will then sell

new figures to neighboring families, leaving the original statue with an

emaciated body. The statues with bonga are called butti;

without bonga they are called tege. Often the magical

substance is placed all around the body with a cloth. The arms and hands are

often highly conventionalized, carved in right angles at the elbows and

shoulders, or missing altogether. The bonga is composed of various

materials, but one of the main ingredients is whitish clay or chalk, which,

for the Teke, represents the bones of their ancestor, thus conveying

protective power. Often it is mixed with the nail clippings or the hair of a

venerated person, with leaves of specific plants, various parts of snakes or

leopards, etc. There are also statues with two faces and double legs;

statues without the cavity, called nkiba; sitting figures with

cavities.

The Teke used the moon-shaped masks -- flat, decorated with abstract

geometric motifs, bisected by a horizontal stripe, colored with white or red

earth, painted black, blue, and brown. They portray an abstractly

interpreted human face. At the same time, the design is a composition of

symbols. Teke masks are worn by members of the kidumu society either

during the funerals of chiefs, or weddings, or important meetings.

|

|

Teke (Anzika, Bakono, Bateke, M’Teke, Tege, Teo,

Tere, Tsio,), both Congo republics and Gabon

Butti statue.

The Teke inhabit the Stenley Pool area, in both Congo republics and also in

Gabon. They are farmers and hunters and live in an area of plateaus covered

by savannah, in villages grouped under a district chief. The Teke believed

in a supreme being, the creator of the universe, called Nzami or

Nziam, but their only cult was an ancestor cult. The power of this

statue was in a magical substance (bonga) contained in the hole made

in the body. Typical is the presence of fine parallel scarification marks on

the cheeks. The butti representing ancestors are believed to

bring success in hunting or trading and to protect against disease. The

healing power of a butti is based on materials with supernatural

qualities determined by the healer or diviner. The magic stuff may be earth

and plant resin mixed with white chalk, small pieces of wood, hair, or other

ingredients.

Materials: wood

Size: 14" x 6" x 6" |

Teke (Anzika, Bakono, Bateke, M’Teke, Tege, Teo,

Tere, Tsio,), both Congo republics and Gabon

Ceremonial Tsaayi

mask. The name of the ethnic group indicates its occupation – that

is, trading – from teke meaning “to buy.” The Teke inhabit the

Stenley Pool area, in both Congo republics, which is an area of plateaus

covered by savannah, in villages grouped under a district chief. They are

farmers and hunters. The Teke believed in a supreme being, the creator of

the universe, called Nziam, but their only cult was an ancestor cult.

This shield like mask is one of the most amazing masks in the whole of

African art, with highly abstract polychrome patterns. The facial features,

eyes, nose, and mouth, are only minor elements in a decorative whole

accentuated by polychrome. At the same time the design is a composition of

symbols. The Teke masquerade dances originally served to confirm and

maintain the social and political structure in a ceremonial context. With

the onset of French colonial rule this tradition began to go into decline,

and it was not until the countries gained independence that it was partly

revived.

Material: wood

Size: 21" x 19" x 3"

|

|

Teke

(Anzika, Bakono, Bateke, M’Teke, Tege, Teo, Tere, Tsio,), both Congo

republics and Gabon Teke

(Anzika, Bakono, Bateke, M’Teke, Tege, Teo, Tere, Tsio,), both Congo

republics and Gabon

Butti statue. The Teke

inhabit the Stenley Pool area, in both Congo republics. They are farmers and

hunters and live in an area of plateaus covered by savannah, in villages

grouped under a district chief. The Teke believed in a supreme being, the

creator of the universe, called Nzami or Nziam, but their only

cult was an ancestor cult. The power of this statue is in a magical

substance (bonga) contained in the sack surrounding the body from

which the head and feet protrude. Typical is the presence of fine parallel

scarification marks on the cheeks. The butti is believed to bring

success in hunting or trading and to protect against disease. The magic

stuff may be earth and plant resin mixed with white chalk, small pieces of

wood, hair, or other ingredients.

Materials: wood, textile, feathers

Size:

|

TOMA

Liberia,

Guinea and Liberia

Settled in the

northwest of Liberia, western Sierra Leone, and eastern Guinea, the 200,000

Toma live in the high-altitude rain forest. They organized their political

and religious life around the poro association. This society was,

among other things, responsible for the initiation of young boys that took

place in the forest, which is particularly dense in the land of the Toma.

When called forth by the landai (landa), a large mask, the

future initiates would leave “on retreat” for the forest for a month. The

landai, a horizontal unusually free, abstract wooden mask, has the mouth

of a crocodile on which human features have been sculpted: a straight nose

underneath arched eyebrows. The jaw is sometimes articulated, sometimes

depicted by a horizontal line that creates a second volume perpendicular to

the first. The top is surmounted by a headdress of feathers and the wearer

looks through the snout. The largest known landai mask was 1.82 m in

height. Its frightening image represented the major forest spirit which made

manifest the power of

poro;

one of its duties was symbolically to devour boys at the end of their

initiation period in order to give them rebirth as men. Only men wore these

masks, which were fitted over the wearer's head horizontally.

The bakrogui, more common and less secret than the landai, are

smaller masks that come in couples. The mask consists of a vertical panel

upon which human features have been inscribed, a bulging nose and forehead,

a beard, and tubular eyes or eyes heightened by metal disks. This mask may

be seen only by members of the poro. Each mask may be thought of as

the spiritual dwelling of an ancestor.

Figures also exist and are kept within each household. They have facial

feature similar to landai masks. |

|

Toma.

Maternity sculprue of mother and twins. Toma.

Maternity sculprue of mother and twins. |

Toma (Loma, Lorma), Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea

Nyangbai or bakrogui

mask. Settled in

the northwest of Liberia, western Sierra Leone, and eastern Guinea, the

200,000 Toma live in the high-altitude rain forest. Their most notable

sculptural forms were wooden masks that combined human and animal features.

This mask presents the wife of the great forest spirit. It is worn directly

over the male wearer’s face. The upper part exhibits simplified (cattle or

antelope) horn shapes and a rounded forehead. Usually such female partners

to big male masks help out at periods of initiation and make an appearance

only at important funerals or crisis.

Material: wood |

Toma

Crest. Toma

Crest. |

Toma Mask |

|

28" x 12" x" 1" |

23" x 10" x 3" |

13" x 6" x 6" Janus faces |

23" x 10" x 3" |

|

TUAREG

Algeria,

Tunisia, Mali, Libya, Burkina Faso and Niger

The Tuareg are a tribal

people of the Sahara. Today more than 300,000 Tuareg live in Algeria,

Tunisia, Mali, Libya, Burkina Faso, and Niger. They speak a Berber

language, Tamarshak, and have their own alphabet. In ancient times, the

Tuareg controlled the trans-Sahara caravan routes, taxing the goods they

helped to convey and raiding neighboring tribes. In modern times, their

raiding was subdued by the French who ruled Algeria. The political

division of Saharan Africa since the 1960s has made it increasingly

difficult for the Tuareg to maintain their pastoral traditions.

Tuareg society distinguishes among nobles,

vassals, and serfs. Slave-stealing expeditions have been abolished, but

the black descendants of former slaves still perform the menial tasks.

Social status is determined through matrilineal descent. Converted by

the Arabs to Islam, the Tuareg have retained some of their older rites.

Among the Tuareg, for example, men—not women—wear a headdress with a

veil.

Many Tuareg starved in droughts in the

1970s, and others have migrated to cities. After leather,

wood is perhaps the most important material in Saharan daily life, and

is used for the poles and beams of the nomads’ tents on which are hung

bags, saddles, bows and whips, as well as bed frames, dishes, cups,

milking bowls, spoons, mortars and pestles. Among the Tuareg

elegantly sculpted cushion supports (ehel) are important items in

any well-appointed household. They were carved by members of the guild

known as enaden, blacksmiths who have been instrumental in the

creation of precisely those things that have forever distinguished the

upper classes of the society from the many vassal populations of the

Tuareg world. Ehel form part of the basic furnishing found in

any upper-class Tuareg’s tent. Ehel are used to pin the mat-woven

walls against the exterior tent-poles.

|

|

Tuareg, Niger

Cushion support (ehel).

Among the Tuaregs of Nigerelegantly sculpted cushion supports are

important items of any well-appointed household. They were carved by members

of the guild known as Enaden, literally meaning ‘the other’, blacksmiths who

have been instrumental in the creation of precisely those things that

distinguished the upper classes of this society from the many vassal

populations of the Tuareg world. The products of the Enaden are among the

most potent of hegemonic symbols – for in sitting reclining upon the pillows

and ehel, Tuareg nobles literally sit and lean upon these artists,

dramatically re-enacting the historical relationship between themselves and

the members of this guild. Tuareg sitting in his tent is to witness the

fullness of his authority and to realize that he is filled with a sense of

personal superiority that cannot be wrested from him.

Material: wood

Size:54" x 6.5" |

|

|

|

Tusyan

(Toussian, Tusia, Tusian, Win)

Burkina Faso

The Tusyan, a small

ethnic group in southwestern Burkina Faso are known especially for large,

rectangular masks (loniaken) with figurative depiction of buffalo

horns or bird’s head on the upper edge. These elements symbolize the totem

animal of the clan to which the mask’s owner belongs. These masks were part

of the Do or Lo cult into which all adolescents were initiated. In present

case the mask is topped with two bird’s heads, representing the grey

hornbill. During biannual ceremonies which were a precondition for marriage,

the boys were given new, secret names associated with birds or wild animals.

About every forty years, a great initiation rite was held in which those

already initiated took part. Such masks were used exclusively at these great

initiation rites.

Material: wood, red Abrus

precatorius seeds

Size: 31" x 21" x 3"

|

UNATTRIBUTED |

|

38" x 17" x 4" 38" x 17" x 4" |

Hemba? Kusu? Luba? |

9" x 3" x 4" 9" x 3" x 4"

|

12" x 8" x 3" |

10 x 6" x 2"

not Ashanti |

|

16" x 6" x 5"

not Ashanti 16" x 6" x 5"

not Ashanti |

|

Possibly, Baule or Guro????

18" x 11" x 7" (no raffia on the mask) |

18" x 12" x 8"

|

24" x 7" x 6" |

WOYO Woyo (Bahoyo, Bawoyo, Ngoyo)

Democratic Republic of

the Congo and Angola's Cabinda Province

A small tribe located both in the Democratic

Republic of the Congo and in Cabinda (province of Angola), the Woyo live on

the Atlantic Ocean coast, north of the estuary of the Zaire River. As early

as the late fifteenth century, their ancient kingdom was known to Europeans

as that of the Ngoyo.

Living along

the coast allows the Woyo to depend on the sea for much of their food. Men

fish in the ocean, collect coconuts, and make palm wine. They also practice

some hunting and do most of their own smithing. Women also fish, mostly in

local ponds. They contribute significantly to the local economy, farming

corn, manioc, bananas, beans, and pineapple. Surplus food is often traded to

inland neighbors for profit under the supervision of local lineage heads

from individual villages.

The Woyo possess a form of writing that has not yet

been studied. A special application of this writing occurs in their “proverb

covers,” the lids of their realistically carved wooden “storied pots,” which

serve as an ingenious means of communication between husband and wife. Woyo

sculpture shows the influence of their Kongo neighbors, while remaining

stylistically distinct. Numerous types of figural sculptures, which are used

in religious ceremonies, are carved from wood. Their sculpture

includes masks of the ndunga, a male society whose dances mark

particular occasions including installations of tribal elders, funerals,

celebrations, or the presence of great danger. The ndunga masks of

the Woyo are characterized by their large size. These masks are worn with

proportionately voluminous costumes of dried banana leaves that fully cover

the dancers’ body. As a general rule, the masks are polychrome; however,

some are painted primarily white. Believed to have symbolic meaning, the

color is related to the concept of the masks’ power and is sometimes

renewed. Their statues often adorned with magical objects called nkissi,

have a triangular-shaped jaw and enlarged eyes.

|

|

Woyo

(Bahoyo, Bawoyo, Ngoyo), Democratic Republic of the Congo and Cabinda

Ndunga dance

mask. The small Woyo people live on the Atlantic Ocean coast, north

of the estuary of the Zaire River. The Woyo possess a form of writing that

has not yet been studied. A special application of this writing occurs in

their “proverb covers,” the lids of their realistically carved wooden

“storied pots.” Woyo sculpture shows the influence of their Kongo neighbors,

while remaining stylistically distinct. Their sculpture includes masks of

the ndunga, a male society whose dances mark particular occasions

including installations of tribal elders, funerals, celebrations, or the

presence of great danger. These masks are worn with voluminous costumes of

dried banana leaves that fully cover the dancers’ body. As a general rule,

the masks are polychrome.

Material: wood

Size: 22" x 12" x 2"

|

Ndunga dance

mask. The small Woyo people live on the Atlantic Ocean coast, north

of the estuary of the Zaire River. The Woyo possess a form of writing that

has not yet been studied. A special application of this writing occurs in

their “proverb covers,” the lids of their realistically carved wooden

“storied pots.” Their sculpture includes masks of the ndunga, a male

society whose dances mark particular occasions including installations of

tribal elders, funerals, celebrations, or the presence of great danger. They

are also agents of social control that operate like secret police. These

masks are worn with voluminous costumes of dried banana leaves that fully

cover the dancers’ body. As a general rule, the masks are polychrome. The

open mouth reveals a decoratively filed incisor. Ndunga dance

mask. The small Woyo people live on the Atlantic Ocean coast, north

of the estuary of the Zaire River. The Woyo possess a form of writing that

has not yet been studied. A special application of this writing occurs in

their “proverb covers,” the lids of their realistically carved wooden

“storied pots.” Their sculpture includes masks of the ndunga, a male

society whose dances mark particular occasions including installations of

tribal elders, funerals, celebrations, or the presence of great danger. They

are also agents of social control that operate like secret police. These

masks are worn with voluminous costumes of dried banana leaves that fully

cover the dancers’ body. As a general rule, the masks are polychrome. The

open mouth reveals a decoratively filed incisor.

Material:

wood

Size: 13" x 8" x 8" |

|

YAKA

Democratic Republic of the Congo

The

Kwango River area (southwest of the Democratic Republic of the Congo) is the

home of some 300,000 highly artistic Yaka people. Yaka or yakala

means “males,” “the strong ones,” thus Bayaka, “the strong people.” The Yaka

society is organized into strong lineage group headed by elders and lineage

headmen. The chief of the lineage had the power of life and

death over lineage members. He was in charge of the cult of the ancestors

and judiciary authority, and it was compulsory that he have large number of

descendants. Chiefs, including dependent village chiefs, regional

overlords, and paramount chiefs, are believed to have extra-human abilities,

ruling the underworld or spiritual realm as well as the ordinary world. A

chief participates in the affairs of witches so that he can tap their power

for the good of the community. On the periphery of the hierarchy,

the “master of the earth” plays an important role during the rites that

accompany the hunt – the primary activity of the men. The Yaka hunters

perform a specific ritual under the direction of the “master of the earth”

to guarantee that they procure game. The Yaka have an initiation, the

n-khanda. A special hut is built in the forest to give shelter to the

postulants during their retreat; the event ends in circumcision, an occasion

for great masked festivities including dances and songs. The n-khanda

is organized every time there are enough eligible youths between ten and

fifteen years of age.

The arts of the Yaka people are very much

alive today. The statues that contain magic ingredients, the

biteki (nkisi), are multi-functional and sometimes have

contradictory roles, for example, they were used to heal and to cause

illness. The medications are placed in the figure’s abdomen, which

is closed up with a resin stopper, or enclosed in small bags hung around the

neck or waist. All nkisi figures are manipulated by

a diviner to activate a force which can either inflict illness or protect

one’s clan from illness or harm, depending upon the particular set of

circumstances. The diviner has an important position in Yaka society because

he owns and activates powerful objects, including some masks, that can

protect or harm.

The Yaka also have statues of chiefs which are

not, however, portraits. These emphasize his authority by representing the

chief, his many wives, his children, and his servants, gather together in

the same shelter. Large, life-size carved figures stand at the entrances of

Yaka initiation huts, the inside walls of which are covered with painted

bark panels. The torso is highly developed; missing extremities

allude to an accident that befell a hero. The phuungu, a statuette

of some 6” belongs to the chief of the patrilinear lineage. The torso is

wrapped in magic ingredients and has an almost spherical shape; often hooked

onto the roof of the hut, it receives libations of blood that activate its

power.

The masks are commonly used. The eastern Yaka mask is called

kakunga (“the chief”) and is considered one of the important masks in

the circumcision ceremony. Other Yaka masks are widely varied in style,

although most of them are polychrome. The nkisi masks have a long,

exaggerated upward-hooked nose, open mouth. Many masks and figures are

remarkable by the turned-up nose. This is a strange but common detail,

and there is no decisive explanation for this nose. One

source supposes that it is an allusion to the elephant's trunk. A long

handle under the chin was held by the dancer. The mask is generally

surmounted by a richly ornamented, abstract construction – sometimes

resembling a Thailand pagoda; sometimes in animal shapes, made of twigs,

covered with fiber cloth, and finally painted. A variant is the broad-nosed

polychrome mask, with round, protruding eyes and square, block-like ears.

These two types of masks were used in initiation ceremonies of the

mukanda or nkanda societies. At the conclusion of the initiation,

the masks were held in front of the faces of the dancers. There are also

animal masks. The masks fulfill several functions: some serve as

protection against evil forces, others ensure the fertility of the young

initiate. Their role consists in frightening the public, healing the sick,

and casting spells. The kholuka mask dances alone at the end of

celebrations. Very popular, featuring globular or tubular eyes, a

protuberant or snub nose, and an open mouth showing its teeth, it sometimes

has a hairdo of branches covered with raffia. All refer to the power of the

elders and their predecessors, and every element of the mask is the plastic

translation of a cosmological term. The colors are those of the rites of

passage; the serpent motif symbolizes the rainbow and the moon.

After undergoing various trials in more or less secret camps, the initiates

appear in the village, dancing and wearing masks prepared for this purpose.

The Yaka use a narrow cylindrical wooden slit-drum with a carved head for

divination purposes. Sometimes the head is Janus form. This instrument, the

main insignia of the diviner, is the focus of a complex system of ritual

institutions concerned with hereditary curses and curing. The slit-drum

functions in a variety of contexts. It is used as a container for preparing

and serving divinatory medicines, but it is also beaten at the funeral of a

diviner.

The

Yaka give an aesthetic touch to many everyday objects such as stools, combs,

pipes, headrests, and musical instruments. |

|

Yaka (Bayaka), Democratic Republic of the Congo

Ceremonial njila figurine.

The arts of the Yaka are very much

alive today. Ceremonial masks and figures are the work of a

sculptor who carries out his art well away from the view of other villagers.

The Yaka have an initiation, the n-khanda. A special hut is built in

the forest to give shelter to the postulants during their retreat; the event

ends in circumcision, an occasion for great masked festivities including

dances and song. The n-khanda is organized every time there are

enough eligible youths between ten and fifteen years of age. The njila

figurine represents a mythological bird. Placed in the interior of the

house, it protects against witches and other enemies that might cause

affliction. It is also placed in sleeping quarters where it functions as a

protective charm with strong fertility connotations. Besides, it is used in

some initiation ceremonies, and may also appear as mask. Its specific

function in the initiation is not clear.

Material: wood, raffia

Size: 17" x 8" x 6" |

Yaka

(Bayaka), Democratic Republic of the Congo

The chest. Yaka

artistic tradition is rich and various, but much of it has been informed by

their neighbors – the Suku, the Kongo, the Holo and the Teke. The

beautifully carved chests of this kind have been used by diviners. This

piece is decorated by mythical subjects.

Material: wood

Size: 38" x 17" x 12" |

Yaka (Bayaka), Democratic Republic of the Congo

The chest. The Yaka

migrated from Angola during the 16th century and settled under

the control of the Kongo kingdom. In the 18th century their lands

were annexed by the Lunda people, but by the 19th century the

Yaka had regained their independence. Yaka society is tightly structured and

headed by a chief of Lunda origin, who delegates responsibilities to

ministers and lineage chiefs. The chests of this kind have been used by

diviners. This beautifully carved piece is decorated by mythical subjects.

Its specific purpose is unknown.

Material: wood

Size: 46" x 12" x 12" |

Yaka (Bayaka), Democratic Republic of the Congo

Mbwoolo

protective figurine.

Yaka means “males,” “the

strong ones,” thus Bayaka, “the strong people.”

The Yaka number about 300,000. They settled along the

middle Kwango River and along the Wamba River, in the southwest of the

country.

The tribe lives principally from hunting, although subsidiary farming is

undertaken by the women. They

cultivate manioc, yams, peas, pineapples and peanuts.

Young

men are expected to pass through various initiation stages, including

circumcision.

Highly artistic people, the Yaka give an aesthetic

touch to many everyday objects such as combs, pipes, musical instruments.

This figurine represents one of the Yaka tribe’s most widespread sculptural

categories. Its function is to protect people against evils. Typical are the

hands touching the chin, squatting posture, and protruding ears.

Material: wood

Size: 18" x 6" x 6" |

|

Yaka (Bayaka) or Suku, Democratic Republic of the Congo

Ceremonial kopa cup. The cups of

this type are supposed to have been used in marriage ceremonies, the bride

drinking palm wine from one side and the bridegroom from the other to seal

their union. Another source relates them to prestige objects connected with

leadership. The kopa was formerly one of the symbols of office

presented to a new chief or lineage headman upon his investiture. No one

else could touch it without proper authority. At the owner’s death, a

kopa was presented to his successor.

Material: wood

Size: 5" x 3" x 3" |

13" x 8" x 5" |

Yaka (Bayaka), Democratic Republic of the Congo

Ceremonial kopa cup. The cups of

this type are supposed to have been used in marriage ceremonies, the bride

drinking palm wine from one side and the bridegroom from the other to seal

their union. Another source relates them to prestige objects connected with

leadership. The kopa was formerly one of the symbols of office

presented to a new chief or lineage headman upon his investiture. No one

else could touch it without proper authority. At the owner’s death, a

kopa was presented to his successor.

Material: wood

Size: 8" x 3" x 3" |

Yaka (Bayaka), Democratic Republic of the

Congo

Statue of the Chief. The

Kwango River area (southwest of the Democratic Republic of the Congo) is the

home of the Yaka and Suku, highly artistic peoples. Their institutions,

political organization, and cultural traditions are almost identical; they

can be differentiated only by the style of their statuary. The arts of the

Yaka numbering about 300,000 are very much alive today. The Yaka have

statues of chiefs which are not, however, portraits. This statue by its

composition is very close to the Yaka statue exhibited in the Museé Royal

de l’Afrique Centrale in Tervuren, Belgium. Its meaning is not known.

Material: wood

Size: 21" x 5" x 5" |

Yaka (Bayaka), Democratic Republic of the Congo

Ceremonial kopa cup. The cups of

this type are supposed to have been used in marriage ceremonies, the bride

drinking palm wine from one side and the bridegroom from the other to seal

their union. Another source relates them to prestige objects connected with

leadership. The kopa was formerly one of the symbols of office

presented to a new chief or lineage headman upon his investiture. No one

else could touch it without proper authority. At the owner’s death, a

kopa was presented to his successor.

Material: wood

Size: 3" x 6" x 4" |

|

Mbwoolo

protective figure. Yaka means “the strong ones," “ba” means people,

thus Bayaka means ”the strong people.” Settled along the length of the

middle Kwango River, in the southwest of the country, they number about

300,000. The men traditionally practiced hunting, while the women

cultivated manioc, yams, peas, pineapples and peanuts. They practice

initiation and circumcision. Highly artistic people, the Yaka give an

aesthetic touch to many everyday objects such as combs, pipes, musical

instruments. The figure represents one of the Yaka tribe’s most widespread

sculptural categories. Typical are the hands touching the chin. Its function

is to protect people against evils. Mbwoolo

protective figure. Yaka means “the strong ones," “ba” means people,

thus Bayaka means ”the strong people.” Settled along the length of the

middle Kwango River, in the southwest of the country, they number about

300,000. The men traditionally practiced hunting, while the women

cultivated manioc, yams, peas, pineapples and peanuts. They practice

initiation and circumcision. Highly artistic people, the Yaka give an

aesthetic touch to many everyday objects such as combs, pipes, musical

instruments. The figure represents one of the Yaka tribe’s most widespread

sculptural categories. Typical are the hands touching the chin. Its function

is to protect people against evils.

Material: wood

Size:

12" x 5" x 5"

|

Yaka (Bayaka), Democratic Republic of the Congo

Yaka kholuka ceremonial mask.

Established in the southwest of DRC, the Yaka number some 300,000

individuals. The men traditionally practiced hunting, while the women

cultivated manioc, yams, peas, pineapples and peanuts. The masks are the

work of a sculptor who carries out his art well away from the initiation

enclosure, also separated from the view of other villagers. The sculptural

composition of this mask is typical of Yaka works. The face features are

painted with bright colors on white background. The ensemble is framed by

the sizeable mass of a coiffure in raffia fiber, this surmounted by a hat

made from armature of vegetable fiber and covered with a resin-coated

tissue. The kholuka mask which is very popular among the Yaka dances

alone at the end of celebrations. The whole mask refers to the power of the

elders and their predecessors, and every element of the mask is the plastic

translation of a cosmological term.

Generally such masks were used only once.

Material: wood, raffia, tissue

Size: 20" x 12" x 13" (30 w raffia) |

12" x 5" x 5" |

YORUBA

Nigeria,

Republic of Benin and Togo

The Yoruba people, numbering over 12 million, are the largest nation

in Africa with an art-producing tradition. Most of them live in southwest

Nigeria, with considerable communities further west in the Republic of Benin

and in Togo. They are divided into approximately twenty separate subgroups,

which were traditionally autonomous kingdoms. Excavation at Ife of

life-sized bronze and terracotta heads and full-length figures of royalty

and their attendants have startled the world, surpassing in their

portrait-like naturalism everything previously known from Africa. The

cultural and artistic roots of the Ife masters of the Classical Period (ca.

1050—1500) lie in the more ancient cultural center of Nok to the northeast,

though the precise nature of this link remains obscure.

Now two-third of the

Yoruba are farmers. Even if they live in the city, they keep a hut close to

the fields; they grow corn, beans, cassava, yams, peanuts, coffee, and

bananas. It is they who control the markets -- along with the merchants and

artisans: blacksmiths, copper workers, embroiderers, and wood sculptors,

trades handed down from generation to generation.

The Yoruba gods form a

true pantheon; the creator god, Olodumare, reigns over almost four hundred

orisha (deities) and nature spirits who live among the rocks, trees,

and rivers. Their figures, more often of Shango (also spelled Sango and

Sagoe), deity of thunder and lightning are carved from wood and kept in

shrines. Sculptors have studios in which apprentices learn the techniques of

the master and his stylistic preferences. Throughout Yorubaland, human

figures are represented in a fundamentally naturalistic way, except for

bulging eyes; flat, protruding, and usually parallel lips; and stylized

ears. Within the basic canon of Yoruba sculpture, many local styles can be

distinguished, down to the hand of the individual artist. Today, Nigeria is

structured by a number of cults. The Gelede cult pays homage to the

power of elderly women. During Gelede festivities, helmet masks

carved in the form of a human face are worn. On top of the head there is

either an elaborate coiffure or a carved representation of a human activity.

The masks of the Epa cult, which is connected with both the ancestors

and agriculture, vary enormously according to the town in which they appear.

The mask proper, roughly globular, has highly stylized features that vary

little; but the superstructure, which may be four feet or more in height, is

often of very great complexity. Generally, they are worn during funerals or

rites of passage ceremonies and characteristically they are composed of many

elements – usually a human-face helmet mask topped by an elaborate standing

figure. When not worn, these masks are kept in shrines where they are

honored with libations and prayers. The Ogboni society brass figures,

called Edan, are cast in pairs and attached to spikes and a chain

runs from head to head to join the pair. They are worn over the shoulders of

Ogboni members as sign of office or as an amulet. Large brass figures,

called onile, are carved as a pair and represent the male and female

aspects of Ile, the earth Goddess. A variety of palm nut containers

used for divination are made with caryatides depicting women. Societies and

cults still hold celebrations today during the many masked festivities in

which costumes of fiber or fabric, masks, music, and dance form one

interlocking whole. The most widely distributed cult is of twins, ibeji,

whose birth among the Yoruba is unusually frequent. An ibeji

statuette is to be made, if one twin died; this ibeji remained with

the surviving twin and was treated, fed, and washed as a living child. Their

effigies, made on the instructions of the oracle, are among the most

numerous of all classes of African sculpture. The equestrian figure is a

common theme in Yoruba wood sculpture. It reflects the

importance of the cavalry in the campaigns of the kings who created the Oyo

Empire as early as the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries. Only

Yoruba chiefs and their personal retainers were privileged to use the horse.

Nevertheless, the rider and the horse remained an important social symbol

and offered an exciting subject for artistic imagination and skill.

The diminutive animal and the dwarfish legs of the horseman are

typical for this type of figures. Carved doors and house posts are found in

shrines and palaces and in the houses of important men. Fulfilling purely

secular functions are bowls for kola nuts, offered in welcoming a guest;

ayo boards for the game, known also as wari, played with seeds or

pebbles in two rows of cuplike depressions; and stools, spoons, combs, and

heddle pulleys. Additional important arts include pottery, weaving,

beadworking and metalsmithing. |

|

Yoruba (Yorba, Yorouba), Nigeria, Benin and Togo

Ibeji (twins) statuettes.

The Yoruba people, numbering over

12 million, are the largest nation in Africa with an art-producing

tradition. The ibeji statuette is a minor art

form. The great frequency of twin births and the heightened infant mortality

rate have found sculptural expression in the Yoruba territory through

ibeji figurines. Sculpted at the sign of the diviner at the death of one

or both twins, they are looked after and venerated by the mothers, who feed

them, clothe them and ritually wash them because they are depositories of

the spirits of the children. A lack of attention could provoke the ire of

the spirits and bring disastrous results. Thus the ibeji are Yoruba

memorials to twins who have died. Twins are believed to be the children of

Shango, the god of thunder and lightning. They are also thought to possess

supernatural powers and share the same soul.

Material: wood, vegetable fiber

Size: 9" x 4" x 3" & 8" x 3" x

4" |

Yoruba

(Yorba, Yorouba), Nigeria, Benin and Togo. Yoruba

(Yorba, Yorouba), Nigeria, Benin and Togo.

Statue |

Yoruba (Yorba, Yorouba), Nigeria, Benin and Togo

Ibeji (twin) female statuette.

The Yoruba people, numbering over

12 million, are the largest nation in Africa with an art-producing

tradition. The ibeji statuette is a minor art

form. Societies and cults still

hold celebrations today during the many masked festivities in which costumes

of fiber or fabric, masks, music, and dance form one interlocking whole. The

most widely distributed cult is of twins, ibeji, whose birth among

the Yoruba is unusually frequent. An ibeji statuette is to be made,

if one twin died; this ibeji remained with the surviving twin and was

treated, fed, and washed as a living child. Their effigies, made on the

instructions of the oracle, are among the most numerous of all classes of

African sculpture. A lack of attention could provoke the ire

of the spirits and bring disastrous results. Thus the ibeji are

Yoruba memorials to twins who have died. Twins are believed to be the

children of Shango, the god of thunder and lightning. They are also thought

to possess supernatural powers and share the same soul.

Material: wood, tissue, beads |

Yoruba (Yorba, Yorouba), Nigeria, Benin and Togo

Olumeye

female figure.

The Yoruba people, numbering over 12 million, are the largest nation in

Africa with an art-producing tradition. Most of them live in southwest

Nigeria, with considerable

communities further west in the Republic of Benin and in Togo,

in an area of forest and savannah.

They are divided into approximately twenty separate subgroups, which were

traditionally autonomous kingdoms. Now two-third of the Yoruba are farmers.

Even if they live in the city, they keep a hut close to the fields; they

grow corn, beans, cassava, yams, peanuts, coffee, and bananas. It is they

who control the markets -- along with the merchants and artisans:

blacksmiths, copper workers, embroiderers, and wood sculptors, trades handed

down from generation to generation. Olumeye means “one who

knows honor” and some Yoruba carvers referred to the female figure as “a

messenger of the spirit” who carries cola and cakes in an offering bowl.

Carvings of this type were used in the reception room of the palace to hold

kola nuts, which were given to the guests as an act of hospitality and for

their refreshment. The hornbills on the top of bowl are symbols of

fecundity.

Material: wood

Size: 27" x 10" x 17

|

|

Yoruba (Yorba, Yorouba), Nigeria, Benin and

Togo

Gelede Mask.

The Gelede cult pays homage

to the power of elderly women who ensure the fertility and

well-being of the community, but who are also held responsible for human

barrenness and death. The mask

festivals called Efe/Gelede are celebrated among the subgroups of the

southwestern Yorubaland. It is usually held between March and May, when the

rains arrive and a new agricultural cycle begins. The masquerades, songs,