|

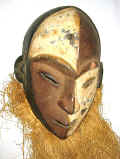

ADOUMA

Gabon

This ethnic

group is located in the Ogooue River region in Gabon. The Duma were the

great boatmen of the Ogooue. They believe in a God who made the world,

in an immortal soul and in retribution for evil; they worship spirits

and ghosts, and are under the sway of sorcerers and secret societies, to

which even the authority of their chiefs must yield. Remarkable are

their masks with flat surface for face, domed forehead, an angular nose,

an interesting interplay of flat, convex, and angular forms. These masks

are mostly polychrome, some with a painted design pattern. For the last

half-century these masks have been used for celebratory dances

associated with the major social rituals. Their former role is less well

documented. |

|

Duma Mask

Material:wood, straw

Size:21" x 11"

x 7" |

The

Duma masks are mostly polychrome. For the last half-century these masks have

been used for celebratory dances associated with major social rituals. Their

former role is less well documented.

Material: wood, tissue, feathers

Size: 14" x 4" x 2" |

Remarkable are the

Duma masks with flat surface for face, domed forehead, an angular nose, and

skillful interplay of flat, convex, and angular forms. The masks of the Duma

are mostly polychrome. For the last half-century these masks have been used

for celebratory dances associated with major social rituals.

Material: wood

Size: 13 x 9" x 2" |

|

AMBETE

(MBETE,

MBEDE, MBETE)

Republic of

Congo, Gabon

The Mbete

claiming a Kota origin live in the middle part of the Republic of Congo

near the frontier of Gabon and in eastern Gabon. In view of the shifting

location of the peoples living in this region, it is impossible to

retrace the precise history of the Mbete culture. Certain ethnological

and sociological aspects of their life are relatively well known, and we

know that the secret societies were numerous and powerful. The Mbete do

not have any centralized political organization; they practice ancestor

worship.

They carved three types of sculpture: heads, busts and full figures.

The latter are thought to have a connection with the ancestor’s cult –

they were either used as reliquaries or placed alongside ancestor bones

in a basket. The massive reliquary figures, statues and masks of the

Mbete are cubist in structure, the stepped hair-dress having

clearly-marked gradations, and the face frequently being painted white.

Heads and busts were probably positioned on poles and placed in front

of the chief’s house. They may have had an apotropaic and emblematic

purpose. Statues are provided with a dorsal, rectangular cavity, or the

body itself may be in the shape of a reliquary chest. The relics could

be set inside the statue. The arms are often fixed to the body and the

hands and feet barely discernible.

Generally the head alone is

sculpted in the round, the arms and lower extremities only roughly

carved out. The faces of the Mbete statues show a prominent forehead

overhanging a hollow receding face with a rectangular mouth and broadly

carved features, so that the original tree-trunk form is still visible.

The shoulders are thrown forward, the arms bent. Frequently, the hairdo,

composed of horizontal loops, is parted by a central crest. |

|

Reliquary

Statue. The Mbete are situated on the border between the Middle

Congo and Gabon, east of the Obamba. In view of the shifting location of the

peoples living in the Ogoue basin (Gabon), it is impossible to retrace the

precise history of the Mbete culture. Certain ethnological and sociological

aspects of their life are relatively well known, and we know that the secret

societies were numerous and powerful. The Mbete do not have any centralized

political organization; they practice ancestor worship, but do not employ

reliquary boxes. Instead, statues are provided with a dorsal cavity, or the

body itself may be in the shape of a reliquary chest. This figure has

definitely connection with the ancestor’s cult. The arms and hands are fixed

to the body. It is hollowed out at the back of the statue into which the

relics were placed.

Material: wood, raffia

Size: 15" x 7" x 7" |

|

ATTYE

(AKYE, AKE,

ANKYE, ATIE, ATTIE, ATYE)

Côte

d’Ivoire

The eastern coast of the Côte d'Ivoire comprises the area of lagoons.

The population here is divided into twelve different language groups

with Akye being one of them. The Akye numbering 55,000 constitute a part

of the Akan group of ethnicities. Before colonization each village was

autonomous and, when threatened, they united to form a 'confederation'.

Usually these people are not governed by chiefs, although a man's social

position is determined by his age.

Early Akan economics revolved primarily around the trade of gold and

enslaved peoples to Mande and Hausa traders within Africa and later to

Europeans along the coast. This trade was dominated by the Asante who

received firearms in return for their role as middlemen in the slave

trade. These were used to increase their already dominant power. Local

agriculture includes cocoa cultivation for export, while yams and taro

serve as the main staples. Along the coast, fishing is very important.

The depleted forests provide little opportunity for hunting. Extensive

markets are run primarily by women who maintain considerable economic

power, while men engage in fishing, hunting and clearing land. Both

sexes participate in agricultural endeavors.

Royal membership among Akan is determined through connection to the

land. Anyone who traces descendence from a founding member of a village

or town may be considered royal. Each family is responsible for

maintaining political and social order within its confines. In the past,

there was a hierarchy of leadership that extended beyond the family,

first to the village headman, then to a territorial chief, then to the

paramount chief of each division within the Asante confederacy. The

highest level of power is reserved for the Asanthene, who inherited his

position along matrilineal lines. The Asantahene still plays an

important role in Ghana today, symbolically linking the past with

current Ghanaian politics.

Akan believe in a supreme god who takes on various names depending upon

the particular region of worship. Akan mythology claims that at one time

the god freely interacted with man, but that after being continually

struck by the pestle of an old woman pounding fufu, he moved far up into

the sky. There are no priests that serve him directly, and people

believe that they may make direct contact with him. There are also

numerous gods (abosom), who receive their power from the supreme god and

are most often connected to the natural world. These include ocean and

river spirits and various local deities. Priests serve individual

spirits and act as mediators between the gods and mankind. Nearly

everyone participates in daily prayer, which includes the pouring of

libations as an offering to both the ancestors who are buried in the

land and to the spirits who are everywhere. The earth is seen as a

female deity and is directly connected to fertility and fecundity.

Woodcarving includes human statues, stools, which are recognized as

"seats" of power, wooden dolls (akua’ba) that are associated with

fertility, and also ivory and brass objects. Lost-wax casting processes

were highly developed among the Akan – both gold and brass were caste.

There are also extensive traditions of pottery and weaving throughout

Akan territory. Kente cloth, woven on behalf of royalty, has come to

symbolize African power throughout the world.

Standing and seated statues with bulbous arms and legs produced by

the Akye show strong Baule influence, but they are very marked by their

distinctive style. Often the hairdo is geometric. What is unusual is

that the relief scarification marks are achieved by insertion of small

wooden plugs into the carving. Representing the forces of female

fecundity, these statues were used in rituals to make these forces work.

This type of statue was known under the tribal name of alangua.

|

|

Alangua -

ceremonial female figure. The eastern coast of the

Côte d'Ivoire comprises the area of lagoons, where the population is divided

into twelve different language groups with Akye being one of them. Usually

chiefs do not govern these people, although a man's social position is

determined by his age. This statue came from the Lagoon region of the

southeastern Côte d’Ivoire and may be attributed to the Akye. The statues of

this type were used in many different ways. The figure could have been owned

by a diviner, for use in conveying messages to the spirit world, or it may

have been prescribed by the diviner to the client. Alternatively, it could

have been intended to represent (and house) a man’s ‘spirit lover’ from the

other world or it may have been displayed at certain traditional dances.

Material: wood

Size: 14" x 5" x 5" |

Alangua -

ceremonial female figure. The eastern coast of the Côte

d'Ivoire comprises the area of lagoons, where the population is divided into

twelve different language groups with Akye being one of them. This statue

came from this region and may be attributed to the Akye. Usually chiefs do

not govern these people, although a man's social position is determined by

his age. Widespread in Lagoon societies is the belief that when people are

born into the world they leave behind a spirit counterpart, or “lover”, in

the other world. This counterpart may become jealous and cause his or her

earthly part impotence, infertility or other misfortune. As part of the cult

individuals lavish attention on beautiful images of their spirit

counterparts. The statues of this type were used in many different ways. The

figure could have been owned by a diviner, for use in conveying messages to

the spirit world, or it may have been prescribed by the diviner to the

client. Alternatively, it could have been intended to represent (and house)

a man’s “spirit lover” from the other world or it may have been displayed at

certain traditional dances. In either case it would have been consecrated to

serve as a dwelling place for a spirit.

Material: wood

Size:

12" x 5" x 5" |

|

ASHANTI

(ASANTE,ACHANTI,

ASHANTE)

Ghana

The Asante region of southern

Ghana is a remnant of the Ashanti Empire, which was founded in the early

17th century when, according to legend, a golden stool descended from

heaven into the lap of the first king, Osei Tutu. The stool is believed

to house the spirit of the Ashanti people in the same way that an

individual's stool houses his spirit after death.

The Asante

number 1.5 million. The early Asante economy depended on the trade of

gold and enslaved peoples to Mande and Hausa traders, as well as to

Europeans along the coast. In return for acting as the middlemen in the

slave trade, the Asante received firearms, which were used to increase

their already dominant power, and various luxury goods that were

incorporated into Asante symbols of status and political office. The

forest surrounding the Asante served as an important source of kola

nuts, which were sought after for gifts and used as a mild stimulant

among the Muslim peoples to the north. In traditional Asante society, in

which inheritance was through the maternal line, a woman's essential

role was to bear children, preferably girls.

The art of

Ashanti can be classified into two main groups: metalwork (casts of

brass or gold using a lost-wax method and objects made of hammered metal

sheets) and woodcarvings. Fertility and children are the most frequent

themes in the wooden sculptures of the Asante. Thus the most numerous

works are akua’ba fertility figures and mother-and-child figures

called Esi Mansa. The acua’ba are dolls with disk-shaped

heads embodying their concept of beauty and carried by women who want to

become pregnant and to deliver a beautiful child. The fame of these

objects derives from a legend asserting that a woman who has worn one

will give birth to a particularly beautiful daughter. A Ghanaian source

indicates another use: when a child disappeared, the acua’ba

statue was placed with food and silver coins at the edge of the forest

to attract the malevolent spirit responsible: the spirit would then

exchange the child for the statue. Sculptured mother-and-child figures

show the mother nursing or holding her breast. Such gestures express

Asante ideas about nurturing, the family, and the continuity of a

matrilineage through a daughter or of a state through a son. The

mother-and-child figures are kept in royal and commoner shrines where

they emphasize the importance of the family and lineage. The Asante are

famous for their ceremonial stools carved with an arched sit set over a

foot, referring to a proverb or a symbol of wisdom. They are usually

made for a chief when he takes office and are adorned with beads or

copper nails and sheets. In rare cases, when the chief is sufficiently

important, the stool is placed in a special room following his death to

commemorate his memory. Asante chairs are based on 17th-century

European models and, unlike stools, do not have any spiritual function.

They are used as prestige objects by important chiefs during festivities

or significant gatherings.

Also

are produced staffs for royal spokesmen, which, like the handles of

state swords, are covered in gold foil. The success of the Ashanti

Empire depended on the trade in gold not only with Europeans at the

coast but also with the Muslim north. Gold dust was the currency,

weighed against small brass weights that were often geometric or were

representations recalling well-known proverbs. Asante weavers developed

a style of weaving of great technical mastery, incorporating imported

silk. The Asante developed remarkably diverse kuduo containers

cast of copper alloys. Kuduo were used in many ways. They held

gold dust and other valuables, but could also be found in important

political and ritual contexts. Some kuduo were buried with their

owners, while others were kept in the palace shrine rooms that housed

the ancestral stools of deceased state leaders. Life and the afterlife,

the present and the past, were enhanced and made more meaningful by the

presence of these elegant prestige vessels. The Asante also cast fine

gold jewelry, as do the Baule of Côte d'Ivoire, who separated from them

in the mid-18th century. The deceased are honored by fired-clay memorial

heads. |

Akua’ba

Doll

Material: wood

Size: 18" x 6" x 5" |

Akua’ba Dolls. In traditional Ashanti society, in

which inheritance was through the maternal line, a woman's essential role

was to bear children, preferably girls to continue the matrilineage.

Fertility and children are the most frequent themes in the wooden sculptures

of the Asante. Such are akua’ba fertility figures. The akua’ba

are dolls with disk-shaped heads embodying their concept of beauty

and carried by women who want to become pregnant and to deliver a beautiful

child. A Ghanaian source indicates another use: when a child disappeared,

the akua’ba statue was placed with food and silver coins at the edge

of the forest to attract the malevolent spirit responsible: the spirit would

then exchange the child for the statue. |

Akua’ba

Doll

Material: wood

Size: 14" x 4" x 3"

|

Akua’ba

Doll

Material: wood

Size: 12" x 6' x 3" |

Akua’ba

Doll

Material: wood

Size: 16" x 6" x 2" |

Akua’ba

Doll

Material: wood

Size: 14" x 5" x 4" |

Akua’ba

Doll

Material: wood

Size: 13" x 3" x 3" |

Maternity

figure. Fertility and children are the most frequent themes in the

wooden sculpture of the Asante. Thus the most numerous works are acua’ba

fertility dolls and mother-and-child figures. In traditional Ashanti

society, in which inheritance was through the maternal line, a woman's

essential role was to bear children, preferably girls to continue the

matrilineage. Such figures show the mother nursing or holding her breast, as

exemplified by this figure. Such gestures express Asante ideas about

nurturing, the family, and the continuity of a matrilineage through a

daughter or of a state through a son. The sculptural emphasis on the child’s

nourishment and security may refer at the same time to the dependence of

each individual on the matrilineage.

Material: wood

Size:

13" x 5" x 6" |

Mmoatia

or “fairy-tale” figure. The Asante region of southern Ghana is a

remnant of the Ashanti Empire, which was founded in the early 17th century

when; according to legend, a golden stool descended from heaven into the lap

of the first king, Osei Tutu. Asante was the largest and most powerful of a

series of states formed in the forest region of southern Ghana by people

known as the Akan. Among the factors leading the Akan to form states,

perhaps the most important was that they were rich in gold. The stretch of

the Atlantic coast now in Ghana became known in Europe as the Gold Coast.

Rather naturalistically carved wood figures in various positions were used

to illustrate legends or stories. They are called mmoatia or

“fairy-tale” figures. The present figure belongs to this group.

Material : wood

Size: 8" x 3" x 2 " |

Mmoatia

or “fairy-tale” figure. The Asante region of southern Ghana is a

remnant of the Ashanti Empire, which was founded in the early 17th century

when; according to legend, a golden stool descended from heaven into the lap

of the first king, Osei Tutu. Asante was the largest and most powerful of a

series of states formed in the forest region of southern Ghana by people

known as the Akan. Among the factors leading the Akan to form states,

perhaps the most important was that they were rich in gold. The stretch of

the Atlantic coast now in Ghana became known in Europe as the Gold Coast.

Rather naturalistically carved wood figures in various positions were used

to illustrate legends or stories. They are called mmoatia or

“fairy-tale” figures. The present figure belongs to this group.

Material : wood

Size: 9" x 3" x 2"

|

Kuduo

box. Inspired by 14th- and 15th century

Arabic-inscribed basins from Mameluk Egypt and other imported Islamic items,

Asante metal casters also drew upon European trade wares in the creation of

luxury containers named kuduo. Possession of elaborately decorated

kuduo was the prerogative of highly positioned chiefs, who used them to

store their treasures, gold dust, and precious beads. Kuduo were also

used to keep sacred objects or sacrificial foods. The lid of this kuduo

and its walls are dominated by bas-reliefs rendering of crocodiles. Some

kuduo were buried with their owners, while others were kept in the

shrine rooms. Life and the afterlife, the present and the past, were

enhanced and made more meaningful by the presence of these elegant prestige

vessels.

Material: copper

alloy

Size: |

Scene from a

legend. The Asante region of southern Ghana is a remnant of the

Ashanti Empire, which was founded in the early 17th century when; according

to legend, a golden stool descended from heaven into the lap of the first

king, Osei Tutu. Asante was the largest and most powerful of a series of

states formed in the forest region of southern Ghana by people known as the

Akan. Among the factors leading the Akan to form states, perhaps the most

important was that they were rich in gold. The stretch of the Atlantic coast

now in Ghana became known in Europe as the Gold Coast. Rather

naturalistically cast figures or scenes were used to illustrate legends or

stories. The present scene is one of them.

It depicts a

procession at a royal festival. The chief is riding in a palanquin under an

umbrella. He must be a person of high status because he is not walking, but

is being carried by 4 carriers and his procession is led by the bearer of

chief's staffs of prestige. The chief is wearing an elaborate head gear, and

he is holding a fly-whisk in his right - presumably to gesture to the

crowds. Included in the procession are a body guard with his sword held

high, musicians with percussive and wind instruments and a dancer with a

mask on the top of his head. The chief is being fanned by a large fan.

Material: brass

Size: 7" x 5" x 4"

THIS ITEM HAS BEEN SOLD

|

| |

This item has been sold

This figurine has flattened head, and facial features

traditional for Ashanti. Purchased by Dr. Raskin near the sacred lake

Bostontwi in Ghana during one of his visits to the area. in the late

1990ies. The lake is so sacred that tribesmen who are fishing or boating on

it are not allowed to use ores and have to row with their hands. There are

very important Ashanti shrines in the area. The figure comes from one of the

villages near a shrine.

Material: wood

size: 6" x 2.5" x 1" |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

BAGA

Guinea and

Guinea-Bissau

Today, the Baga people, 60,000

in total, occupy the northern coast of Guinea and the southern coast of

Guinea-Bissau. They live in the marshy area flooded six months of the

year, during which time the only way to get around is by a dugout canoe.

They live in villages divided into two to four quarters, which are in

turn divided into five or six clans. Traditionally, the village is

headed by the eldest member of each clan.

The Baga are farmers; women primarily

cultivate swamp varieties of rice in wet paddies along the coast.

Cotton, gourds, millet, oil palms, okra, sesame, and sorghum are locally

grown products that help to round out the Baga diet.

The men also fish and grow cola nuts.

Spiritually, they believe in a single god, known as

Kanu,

assisted by a male and female spirits. The only fundamental ritual is

initiation. Before burial, the dead are displayed in a sacred wood and

their belongings are buried.

Baga had rich traditions of

multifunctional masks and sculpture, many of which were suppressed with

the advent of Islam. The best known of these is the massive Nimba (or

Dumba) mask, with its great cantilevered large nose, a large pair of

breasts, crested head supported

on the upper part of a female torso, carved so as to rest on the

shoulders of the wearer, his body hidden in raffia fiber. The mask can

also stand on four legs. Sterile women in the Simo secret society

invoked it as the Mother of Fertility, and it was used at the

first-fruit (rice) rituals, symbolically associating female fertility

with the increase of the grain. This mask appears at the harvest and

threshing of the rice crop, is worn by dancers at birth, marriages and

other joyful ceremonies. This mask represented the very essence of Baga

dignity and culture. The Simo society utilized very large polychrome

masks (often more than 5 feet tall), known as banda or boke

which are used in fertility rituals by this society, played a part

during the dry season, after the rice harvest, and at funerals. It has

an elongated human face with the jaws of a crocodile, the horns of an

antelope, the body of a serpent and the tail of a chameleon.

Baga craftsmen also carve

anok, a-tscol or elek, bird heads with human features that

were used at harvest time and funerary rites, also by the members of the

Simo society. Every family owns an elek, which is part of the family

shrine, together with other objects: stones, vine twigs and bark

reddened by cola nuts, dead scorpions or jaws of crabs, and a fly

swatter, important for purification ceremonies and indispensable in the

hunt for witches. The elek represents the lineage of which it is

protector and the most visible sign. It punishes the guilty, for it

a;one is able to pursue witches wherever they may be.

Baga snake headpiece can be up

to 260 cm high and typically display undulation, polychrome decoration

and sometimes have eyes inset with glass. It is an emblem of Bansonyi,

men’s secret association. This headpiece, also called bansonyi,

presents a python standing upright. Bansonyi lives in the sacred forest

and emerges when it is time to begin the boys’ coming-of-age rites. As

receptacle for the most powerful spirit, bansongyi is believed to

be the strongest adversary of sorcery and destructive forces that could

endanger the well-being of the village. Bansongyi also appears at

the funeral celebrations of the most important members of the community.

They were held on the shoulders of a dancer. There are also other masks

combining human and animal features.

The Baga also produced statues

on round columns, called tambaane, tsakala, or kelefa:

extremely large head, compressed on both sides, in angular, stylized

construction; jutting nose; arms without hands, or hands resting under

the chin. They were kept in round huts by the Simo society.

Tall drums supported by a human

figure are also carved. |

Tonkongba headdress. The

Tonkongba headdress can be seen as a three-part form, including a

helmet in the center, a long snout protruding from the front, and, a pair of

flat horns usually connected at their tips. It is not known much about the

use of these headdresses. Our knowledge concerning the Tonkongba’s

function is complicated by a number of factors, including the extreme

secrecy enveloping the sculpture and the probability that it was used in

different ways by different groups. No doubt, it served both as a shrine

figure and as a dance headdress. According to some sources, the Tonkongba

appeared on any special occasion when a sacrifice was involved, for example,

at a funeral. It danced at sunrise. When Tonkongba came out, the

people would hang tobacco leaves and fowl on its costume as tribute.

Material: wood

Size: 35" x 10" x 7"

|

Nimba

(d’mba) mask.

The various peoples known as Baga and numbering some 65,000

occupy a narrow stretch of marshy lowland along the

Atlantic lagoons of the Republic of Guinea. They grow rice in the marshy

area flooded six months of the year, during which time the only way to get

around is by a dugout canoe. The men also fish and grow cola nuts. They

believe in a single god who is assisted by a male and a female spirit. The

nimba masks are among the most imposing of all African masks. It

represents the idea of the fertile woman. The exaggerated, pendulous breasts

are typical for these masks, which had a double function: sterile women in

the Simo society invoked it as a goddess of fertility, and it was

used at the first-fruit (rice) rituals, symbolically associating female

fertility with the increase of the grain. The masks are used by dancers at

birth, marriages, harvest festivals and other joyful ceremonies.

Material: wood

Size: 40" x 21" x 12"

|

Female Figure.

The various peoples known as Baga and numbering some 65,000

occupy a narrow stretch of marshy lowland along the Atlantic lagoons of the

Republic of Guinea. This marshy

area is flooded six months of the year, during which time the only way to

get around is by a dugout canoe. Their villages are traditionally headed by

the eldest members of each clan. The men fish and grow cola nuts; the women

grow rice. Spiritually, they believe in a single god, known as

Kanu,

assisted by a male and female spirits. The only fundamental ritual is

initiation. The female figure is important in Baga art. This standing figure

of rather naturalistic form represents an initiated young woman. Female

figures of this type were used by many of the adult women’s organizations.

Material: wood

Size:

39" x 10" x 10"

|

Female drum (a-ndef). Among the

Baga female power is demonstrated in drums that are carved in the form of a

kneeling woman who supports the instrument. Owned by the woman’s A-Teken

organization, such drums are played by women at annual initiations, the

funerals of association members, their daughters’ weddings, and the

reception of distinguished visitors. The woman supporting the drum reflects

the female role as “bearer” in Baga culture. Women carry on their heads huge

clay vessels filled with water and large baskets of rice. Among the northern

Baga, the a-ndef , the large cariatide drums with the small drum

barrel were the exclusive property of women’s a-Tekan association.

Material: wood

Size: 44" x 11" x 12"

|

Bansonyi headpiece.

Today, the Baga people, 60,000 in total, occupy the northern coast of Guinea

and the southern coast of Guinea-Bissau. Bansonyi is the man’s secret

society that unites autonomous villages of the Baga people. Its emblem is a

polychrome headpiece, called Bansonyi that is carved in the form of a

python standing upright. It embodies the snake-spirit a-Mantsho-na-Tshol

(“master of medicine”). Among most Baga subgroups, only adolescent males

learn the secrets of the snake-spirit during the initiation, which marks the

passage to adult status. Bansonyi lives in the sacred forest and

emerges when it is time to begin the boys’ coming-of-age rites. Bansonyi

is believed to be the strongest adversary of sorcery and destructive forces

that could endanger the well-being of the village. It is especially

protective of the boys during their initiation into adult society.

Bansonyi also appear at the funeral celebrations of the most important

members of the community.

Material: wood

Size:43" x 7" x 6" |

Elek (composite figure of bird and

human). (???, may be Senufo)

Every Baga family owns an elek, named also

anok

or a-tscol, which is part of the family shrine,

together with other objects: stones, vine twigs and bark reddened by cola

nuts, dead scorpions or jaws of crabs. Eleks are

bird birds with human features that were

used at harvest time and funerary rites, also by the members of the Simo

society. Activated by sacrifices, the elek are

regularly brought out at night. It punishes the guilty, for it alone is able

to pursue witches wherever they may be. This elek is a particularly well

preserved and intricately carved example of Baga sculpture.

Material: wood

SOLD

Size:

26" x 23" x 7" |

A Monumental Banda or boke mask.

The only fundamental ritual

among the Baga is initiation. These people had rich traditions of

multifunctional masks and sculpture, many of which were suppressed with the

advent of Islam. The Simo society utilized very large polychrome masks

(often more than 5 feet tall), known as banda or boke which

were used in fertility rituals by this society, played a part during the dry

season, after the rice harvest, and at other occasions. The banda mask

represents a high rank in the Simo society, and is feared

accordingly. It is worn on the head, horizontally and at a slant. At its

approach all those not initiated flee horror-struck into their huts for

protection. This mask is an elegant composite of animal and human features,

including the jaw of a crocodile, the face and coiffure of a human being,

the horns of an antelope, the body of a snake, and the curling tail of a

chameleon.

Material:

wood

Size:

55" x 15" x 10"

Similar mask sold at Bonhams May 13, 2010 Auction

$12,000

Similar masks described in Art of the Baga by Frederik

Lamp pp 144-149 |

|

BAMBARA

(BAMANA,

BANMANA)

Mali

The Bambara numbering 2,500.000 million form the largest ethnic

group within Mali. The triangle of the Bambara region, divided in two

parts by the Niger River, constitutes the greater part of the western

and southern Mali of today. The dry savanna permits no more than a

subsistence economy, and the soil produces, with some difficulty, corn,

millet, sorghum, rice, and beans. Their traditions include six male

societies, each with its own type of mask. Initiation for men lasts for

seven years and ends with their symbolic death and their rebirth.

The ntomo society is for young boys before circumcision.

There are two main style groups of their masks. One is characterized by

an oval face with four to ten horns in a row on top like a comb, often

covered with cowries or dried red berries. The other type has a ridged

nose, a protruding mouth, a superstructure of vertical horns, in the

middle of which or in front of which is a standing figure or an animal.

The komo is the custodian of tradition and is concerned

with all aspects of community life -- agriculture, judicial processes,

and passage rites. Its masks are of elongated animal form decorated with

actual horns of antelope, quills of porcupine, bird skulls, and other

objects. Their headdress, worn horizontally, consists of an animal,

covered with mud, with open jaw; often horns and feathers are attached.

Masks of the kono, which enforces civic morality, are also

elongated and encrusted with sacrificial material. The kono masks

were also used in agricultural rituals, mostly to petition for a good

harvest. They usually represent an animal head with very long open snout

and long ears standing in a V from the head, often covered with mud.

The tji wara (Tji wara)

society members use a headdress representing, in the form of an

antelope, the mythical being who taught men how to farm. The word tji

means “work” and wara means “animal,” thus “working animal.”

There are male and female antelopes with vertical or horizontal

direction of the horns. The dancers appeared in pairs (a man and a woman

– an association with fertility) holding two sticks in their hands,

their leaps imitating the jumps of the antelopes.

The kore, representing the highest level concerned with

the sky and with the bringing of rain to make the crops grow, employs

masks representing the hyena, lion, monkey, antelope, and horse. In

addition there are masks of the nama, which protect against

sorcerers.

The size of the statue may vary from 12 inches to 4 feet. The

figures are usually standing or sitting females with a dignified air,

some holding a child. Some have the arms separated from the body, flat

palms facing forward, the hands sometimes attached to the thighs. They

may have crest-like hairdos with several braids falling on their

breasts. In the same style, representations of musicians and of

lance-carrying warriors are found. There are also carvings with Janus

head. Ancestor figures of the Bambara clearly derive from the same

artistic tradition as do many of those of the Dogon. Rectangular

intersection of flat planes is a stylistic feature common to Bambara and

Dogon sculpture. |

Kore antelope mask.

The 1.9 to 2.5

million Bambara live in the region

around Bamako, the capital of Mali. They form the largest

ethnic group within the country. The Bambara live principally from

agriculture, with some subsidiary cattle rearing in the north of their

territory. The Bambara have a very complex cosmology.

They believe in existence

of spiritual forces, which are activated by individuals, who are capable to

create an atmosphere of harmony. They excelled in three types of sculpture:

stylized antelope headdresses, statues, and masks. This antelope mask is

associated with the Kore men’s secret society which organized young

farmers.

This society employs masks representing the hyena, lion, monkey,

antelope, and horse.

The mask functioned at agricultural activity

such as supplication for rain. The Kore society seems to be

disappearing in Bambara communities.

Material: wood Size: 26" x 10" x 8" |

Kore antelope mask.

The 1.9 to 2.5

million Bambara live in the region

around Bamako, the capital of Mali. They form the largest

ethnic group within the country. The Bambara live principally from

agriculture, with some subsidiary cattle rearing in the north of their

territory. The Bambara have a very complex cosmology.

They believe in existence

of spiritual forces, which are activated by individuals, who are capable to

create an atmosphere of harmony. They excelled in three types of sculpture:

stylized antelope headdresses, statues, and masks. This antelope mask is

associated with the Kore men’s secret society which organized young

farmers.

This society employs masks representing the hyena, lion, monkey,

antelope, and horse.

The mask functioned at agricultural activity

such as supplication for rain. The Kore society seems to be

disappearing in Bambara communities.

Material: wood,

cowries,

animal hair

Size: 31" x 10 " x 8"

|

Dyonyeni female figure.

The Bambara excelled in three types

of sculpture: stylized antelope headdress, statues, and masks. The basic

characteristic of all their carvings is the use of bold volumes, often in

angular interplay, with semiabstract over-all composition.

The dyonyeni female figures are thought to be associated with either

the Dyo or the Kwore society. For the Bambara, the mother

figure is the embodiment of Faro, the goddess of water and mother of

all mankind. She manifests herself in rain and rainbow, or thunder and

lightning. The figures usually have geometrical features such as large

conical or rounded breasts. The blacksmith members of the Dyo society

used them during dances to celebrate the end of the initiation ceremonies.

They were handled, held by dancers and placed in the middle of the

ceremonial circle.

Material: wood

Size: 44" x 10" x 9" |

Female figure (joneyeleni or nyeleni).

While creating such freestanding figures depicting nubile young women, the

sculptors portrayed the Bambara symbolic ideal of feminine beauty. The

figures are rubbed with oil, clothed and adorned with beads and other

ornaments to resemble Bambara women dressed for festive occasions. Sculpted

figures of this type were used in the context of Jo activities. Jo was a

traditional institution concerned with maintaining social, spiritual and

economic harmony within the community. Unlike other Bambara institutions,

women as well as men were members. Newly initiated male youths displayed the

nyeleni figures during performances of Jo songs and dances.

Material: wood

Size: 34" x 7" x 9" |

Kore

monkey mask.

The

Bambara

live in the region around Bamako, the

capital of Mali. They form the largest ethnic group within

the country. The Bambara maintain many of their ancient religious rites,

which are principally concerned with agriculture.

The masks of the Bambara can be classified

according to the secret societies in which they were used, namely the

N’tomo, Kore, Kono, and Komo. Through the six

levels of education the initiate learns the importance of knowledge and

secrecy, is taught to challenge sorcery, and learns about the dual nature of

mankind, the necessity for hard labor in the production of crops, and the

realities of surviving from day to day.

The Kore society, concerned with the

sky and with the bringing of rain to make the crops grow, employs masks

representing the hyena, lion, monkey, antelope, and horse. This monkey mask

is one of them.

Material: wood

Size:

11" x 9" x 5" |

Material: wood

Size: 15" x 8" x 3" |

Hyena mask. The Bambara are dignified

people, proud of their warlike past. Nowadays they live principally from

agriculture, with some subsidiary hunting and cattle rearing in the northern

part of their territory. They strongly uphold their ancient tribal customs

against Islam and Christianity. This is a hyena mask used by the

agricultural Kore society. The Kore society is a rigidly

stratified male initiation group that seeks to bring men to peace with their

spirits. Its members achieved a degree of spiritual knowledge that enabled

them to experience a mystic union with divine power and enter a perpetual

cycle of reincarnation. The hyena was the society’s guardian animal. It

symbolizes fallible human wisdom. The masks of this type were used both at

initiations and at agricultural festivities, in supplications for the

fecundity of the earth and sometimes for rain.

Material: wood

Size: 12" x 7" x 6" |

Male Tji wara (antelope headdress).

The Bambara, largest and most powerful tribe in

the Western Sudan live in the open savanna to the southwest of the Dogon.

Though they are Moslem, they maintain many of their ancient religious rites,

which are principally concerned with agriculture and the fertility of the

land. Among

the best known of the Bambara associations is the Tji Wara. In the

past the purpose of the Tji Wara association was to encourage

cooperation among all members of the community to ensure a successful crop.

In recent time, however, the Bambara concept of tji wara has become

associated with the notion of good farmer, and the tji wara

masqueraders are regarded as a farming beast. The Bambara sponsor farming

contests where the tji wara masqueraders perform. Always performing

together in a male and female pair, the coupling of the antelope

masqueraders speaks of fertility and agricultural abundance. According to

one interpretation, the male antelope represents the sun and the female the

earth. The antelope imagery of the carved headdress was inspired by a

Bambara myth that recounts the story of a mythical beast (half antelope and

half human) that introduced agriculture to the Bambara people. The dance

performed by the masqueraders mimes the movements of the antelope.

Material: wood

SOLD

Size: 27" x 14" x 4" |

Very rare in Bambara

masks human features are without animal attributes and feathers are not

typical.

Material: wood, feathers

Size: 14" x 6" x 6" |

Male figure. No description

Material: Wood

Size:25" x 7" x

4" |

Seated male figure

Material: wood

Size: 53" x 9" x 8"

|

Possibly a part of tji wara

Material: wood

Size: 20" x 3" x 4"

|

Seated mother-and-child figure (gwandusu).

The basic characteristic of Bambara carvings is the use of bold volumes,

often in angular interplay, with semiabstract over-all composition.

Gwan was a Bambara society concerned with human fertility

and childbearing. Its Major female figure was a woman holding a baby; the

name of this figure, gwandusu, is said to mean “one who has strength

and can achieve greatness.” The position of this mother-and-child figure

sitting on the ground is rare.

Material: wood

Size: 25" x 14" x 4"

|

Kore

antelope mask. The

Bambara live in the

region around Bamako, the capital of Mali. They form the

largest ethnic group within the country. The Bambara live principally from

agriculture, with some subsidiary cattle rearing in the north of their

territory. The Bambara have a very complex cosmology.

They believe in existence

of spiritual forces, which are activated by individuals, who are capable to

create an atmosphere of harmony. They excelled in three types of sculpture:

stylized antelope headdresses, statues, and masks. This antelope mask is

associated with the Kore men’s secret society which organized young

farmers.

This society employs masks representing the

hyena, lion, monkey, antelope, and horse.

The mask functioned at agricultural

activity such as supplication for rain. The Kore society seems to be

disappearing in Bambara communities. Kore

antelope mask. The

Bambara live in the

region around Bamako, the capital of Mali. They form the

largest ethnic group within the country. The Bambara live principally from

agriculture, with some subsidiary cattle rearing in the north of their

territory. The Bambara have a very complex cosmology.

They believe in existence

of spiritual forces, which are activated by individuals, who are capable to

create an atmosphere of harmony. They excelled in three types of sculpture:

stylized antelope headdresses, statues, and masks. This antelope mask is

associated with the Kore men’s secret society which organized young

farmers.

This society employs masks representing the

hyena, lion, monkey, antelope, and horse.

The mask functioned at agricultural

activity such as supplication for rain. The Kore society seems to be

disappearing in Bambara communities.

Material: wood

Size: 32" x 8" x 9" |

Dyonyeni female figure.

The Bambara excelled in three types

of sculpture: stylized antelope headdress, statues, and masks. The basic

characteristic of all their carvings is the use of bold volumes, often in

angular interplay, with semiabstract over-all composition.

The dyonyeni female figures are thought to be associated with either

the Dyo or the Kwore society. For the Bambara, the mother

figure is the embodiment of Faro, the goddess of water and mother of

all mankind. She manifests herself in rain and rainbow, or thunder and

lightning. The figures usually have geometrical features such as large

conical or rounded breasts. The blacksmith members of the Dyo society

used them during dances to celebrate the end of the initiation ceremonies.

They were handled, held by dancers and placed in the middle of the

ceremonial circle.

Material: wood

Size: 38" x 10" x 8" |

|

BASSA

Liberia

The Bassa, one of the largest Kru-speaking

peoples in the central coastal region and adjacent hinterland of

Liberia, have been strongly influenced by the Mende-speaking neighbors,

especially the Dan and Kpelle. Their economy is based on rice which they

cultivate around small villages which have a population around two

hundred. Bassa artistic tradition has been also influenced by their

north-eastern neighbors, the Dan, who live on the Côte d’Ivoire. The

Bassa have several female and male societies, including chu-den-zo,

to whom gela (geh-naw) masks belong. Bassa carvers are

famed for their gela masks worn during

the no men's society ceremonies when

the wearer of the mask moves with feminine and elegant grace. The

masqueraders entertain the spectators when initiated boys return from

bush camp, when important guests visit the village, and on other festive

occasions. The dancer wears the mask, which is attached to a woven

framework, on his forehead, and looks through a slit in the fabric which

is part of the costume that covers his head and upper body. Because they

are fixed on a framework, the interior of most such masks shows no signs

of wear.

Bassa sculptures also bare similarity to

Dan and display monumental and solemn qualities combined with skillful

carving. Figures of dogs carved with a human face on the side, as well

as stools, are known to exist, although the purpose of the dog statue

remains unknown. |

|

Geh-naw ceremonial mask.

Bassa artistic tradition has been influenced by their northeastern

neighbors, the Dan. With graceful, gliding dances the geh-naw

masqueraders entertain the spectators when initiated boys return from bush

camp, when important guests visit the village, and on other festive

occasions. The dancer wears the mask, which is attached to a woven

framework, on his forehead, and looks through the slit in the fabric, which

is part of the costume that covers his head and upper body. The geh-naw

masks are public entertainers who perform when the boys return from the bush

schools, but also on many other occasions, such as the visits of important

guests or on public holidays. The mask is intended to convey a sense of

grace and serenity.

Material: wood

Size: 10" x 7" x 3"

|

|

BAULE

(BAOULE,

BAWULE)

Côte d'Ivoire

The Baule people, known as one of the largest ethnic group in

the Côte d'Ivoire, have played a central role in twentieth-century

Ivorian history. They waged the longest war of resistance to French

colonization of any West African people, and maintained their

traditional objects and beliefs longer than many groups in such constant

contact with European administrators, traders, and missionaries.

According to a legend, during the eighteenth century, the queen, Abla

Poku, had to lead her people west to the shores of the Comoe, the land

of Senufo. In order to cross the river, she sacrificed her own son. This

sacrifice was the origin of the name Baule, for baouli means “the

child has died.” Now about one million Baule occupy a part of the

eastern Côte d'Ivoire between the Komoé and Bandama rivers that is both

forest and savanna land. Baule society was characterized by extreme

individualism, great tolerance, a deep aversion toward rigid political

structures, and a lack of age classes, initiation, circumcision,

priests, secret societies, or associations with hierarchical levels.

Each village was independent from the others and made its own decisions

under the presiding presence of a council of elders. Everyone

participated in discussions, including slaves. It was an egalitarian

society. The Baule compact villages are divided into wards, or quarters,

and subdivided into family compounds of rectangular dwellings arranged

around a courtyard; the compounds are usually aligned on either side of

the main village street. The Baule are agriculturists; yams are the

staple, supplemented by fish and game; coffee and cocoa are major cash

crops. The importance of the yam is demonstrated in an annual harvest

festival in which the first yam is symbolically offered to the

ancestors, whose worship is a prominent aspect of Baule religion. The

foundation of Baule social and political institutions is the matrilineal

lineage; each lineage has ceremonial stools that embody ancestral

spirits. Paternal descent is recognized, however, and certain spiritual

and personal qualities are believed to be inherited through it. The

Baule believe in an intangible and inaccessible creator god, Nyamien.

Asie, the god of the earth, controls humans and animals. The spirits, or

amuen, are endowed with supernatural powers. Religion is founded

upon the idea of death and the immortality of the soul. Ancestors are

the object of worship but are not depicted.

Baule art is sophisticated and stylistically diverse. Non

inherited, the sculptor’s profession is the result of a personal choice.

The Baule have types of sculpture that none of the other Akan peoples

possess. Wooden sculptures and masks allow a closer contact with the

supernatural world. Baule statues are usually standing on a base with

legs slightly bent, with their hands resting on their abdomen in a

gesture of peace, and their elongated necks supporting a face with

typically raised scarification and bulging eyes. The coiffure is always

very detailed and is usually divided into plaits. Baule figures answer

to two types of devotion: one depicts the “spiritual” spouse who, in

order to be appeased, requires the creation of a shrine in the personal

hut of the individual. A man will own his spouse, the blolo bian,

and a woman her spouse, the blolo bla. The Baule believe that

before they were born into the world they existed in a spirit world,

where each one had a mate. Sometimes that spirit mate becomes jealous of

their earthly mate and causes marital discord. When this happens, a

figure depicting the other world spouse is carved and placated with

earthly signs of attention.

The Baule are also noted for their fine wooden sculpture,

particularly for their ritual figures representing spirits; these are

associated with the ancestor cult. The Baule have also created monkey

figures gbekre that more or less

resemble each other. Endowed with prognathic jaw and sharp teeth and a

granular patina resulting from sacrifices, the monkey holds a bowl or a

pestle in its paws. Sources differ on its role or function: some say it

intervenes in the ritual of divination, others that it is a protection

against sorcerers, or a protective divinity of agrarian rites, or a bush

spirit. The figures and human masks are elegant -- well polished, with

elaborate hairdressings and scarification.

Masks correspond to three types of dances: the gba gba,

the bonu amuen, and the goli. They never represent the

ancestors and are always worn by men. The gba gba is used at the

funerals of women during the harvest season. It celebrates beauty and

age, hence its refined features. The double mask represents the marriage

of the sun and the moon or twins, whose birth is always a good sign. The

bonu amuen protects the village from external threats; it obliges

the woman to a certain discipline; and it appears at the commemorations

of death of notables. When they intervene in the life of the community,

they take the shape of a wooden helmet that represents a buffalo or

antelope and which is worn with a raffia costume and metal ankle

bracelets; the muzzle has teeth which incarnate the fierce animal that

is to defend the group. The very characteristic, round-shaped “lunar”

goli is surmounted by two horns. Celebrating peace and joy, they

would sing, dance, and drink palm wine. In the procession, the goli

preceded the four groups of dancers, representing young adolescents. The

goli would be used on the occasion of the new harvest, the visit

of dignitaries, or at the funerals of notables. Boxes for the mouse

oracle (in which sticks are disturbed by a live mouse, to give the

augury) are unique to the Baule, whose carvers also produce heddle

pulleys, combs, hairpins, and gong mallets. |

Female bush spirit figure or mbra.

Around 1 million Baule occupy a part of the central Cote d’Ivoire that is

both forest and savanna land. They came to this territory in the 18th

century, an area previously the home of Guro.

Statues were mostly

used for two purposes: the first was to incarnate a spirit of the bush,

asie usu or mbra; the second was to represent a spouse from the

other world, blolo bla or blolo bian.

According to

the Baule beliefs,

Asie usu (mbra) are extravagant

creatures that live in the bush and occasionally make contacts with human

beings. They are male and female, have colorful personalities, and often

have personal names. Therefore their figures are made in pairs. These

spirits are mischievous, but, if properly honored, will grant fruitful

harvests and hunts. They sometimes express desire, through the village

diviner, to be associated with a specific person. A figure is then sculpted

and worshipped in the house of the designated individual.

Material: wood

Size: 25" x 8" x 7"

|

Baule (Baoule, Bawule)

Côte

d’Ivoire

Male bush

spirit figure or mbra.

Baule statues were mostly used for two

purposes: the first was to incarnate a spirit of the bush, mbra or

asie usu; the second was to represent a spouse from the other world.

According to

the Baule beliefs,

mbra live in the bush and occasionally

make contacts with human beings. They are male and female, have colorful

personalities, and often have personal names. Therefore their figures are

made in pairs. Mbra is a Baule cult used for divination. Only certain

families have mbra, having acquired it in past generation. These

spirits are mischievous, but, if properly honored, will grant fruitful

harvests and hunts. They sometimes express desire, through the village

diviner, to be associated with a specific person. A figure is then sculpted

and worshipped in the house of the designated individual.

Material: wood,

cloth

Size: 23" x 8" x 8"

|

Mblo

dance mask.

The Baule people occupy a

part of the Côte d'Ivoire between the Komoé and Bandama Rivers that is both

forest and savanna land. Baule society was characterized by extreme

individualism, great tolerance, a deep aversion toward rigid political

structures, and a lack of age classes, initiation, circumcision, priests,

secret societies, or associations with hierarchical levels. Each village was

independent from the others and made its own decisions under the presiding

presence of a council of elders. Everyone participated in discussions,

including slaves. It was an egalitarian society. Ancestors are the object of

worship but are not depicted. This

type of masks used in mblo dances is one of the oldest of Baule art

forms. These dances offer psychological relief in times of stress. The mask

is usually a portrait of a particular known individual. Lustrous curving

surfaces, suggesting clean, healthy skin, are set off by delicately textured

zones representing coiffures, scarifications, and other ornaments. The faces

are idealized.

Material: wood

Size: 16" x 9" x 5"

|

Mblo

dance mask. The

Baule people occupy a part of the Côte d'Ivoire between the Komoé and

Bandama Rivers that is both forest and savanna land. Baule society was

characterized by extreme individualism, great tolerance, a deep aversion

toward rigid political structures, and a lack of age classes, initiation,

circumcision, priests, secret societies, or associations with hierarchical

levels. Each village was independent from the others and made its own

decisions under the presiding presence of a council of elders. Everyone

participated in discussions, including slaves. It was an egalitarian

society. Ancestors are the object of worship but are not depicted.

This type of masks used in mblo dances

is one of the oldest of Baule art forms. These dances offer psychological

relief in times of stress. The mask is usually a portrait of a particular

known individual. Lustrous curving surfaces, suggesting clean, healthy skin,

are set off by delicately textured zones representing coiffures,

scarifications, and other ornaments. The faces are idealized.

Material: wood

Size: 21" x 9" x 5"

|

Kplekple

mask. This mask belongs to a group of

various types of masks known as goli. Goli is a day-long

spectacle that normally involves the whole village and includes, besides the

appearance of masks, music played on special instruments, and, ideally, the

joyous consumption of a great deal of palm wine. The goli masks are

considered intercessors with supernatural forces, which can have a positive

influence on human affairs, or, if not appeased, a negative one. The

kplekple masqueraders appear at dawn and again, briefly, during early

afternoon and evening, to announce the arrival of the father (goli glin)

or mother (kpwan). The basic Goli costume presents a netted

shirt and trousers covering the arms, legs, and torso; ankle rattles; a

raffia cape that hangs from the mask, a raffia skirt, and a whole animal

hide on the back. The mask is worn by young men with a goatskin over their

back, who perform a lively dance.

Material: wood

Size: 34" x 24" x 5"

|

Figure of the monkey god Gbekre.

The Baule possess a figure with the head of a monkey representing one of the

humbler gods. It is called Gbekre or Mbotumbo, a god with

several tasks, for he is both judge of hell and helper of those in need,

protector of the living against their enemies. Theese so-called

“mendicant monkey” figures are very different in style of other Baule

sculptures. If the ancestor-cult statues are often characterized by refined

and detailed carving, the wood stained and often polished, the gbekre

are very different. They are roughly carved in unstained wood. They combine

human and animal traits in such a way that it is nearly impossible to

separate them. Besides, they are used for many different cults, for a trance

divination cult among them. Women are forbidden to see some of them, others

are openly shown.

Material: wood, rafia

Size: 20" x 6" x 6" |

Female bush spirit figure or mbra.

Around 1 million Baule occupy a part of the central Cote d’Ivoire that is

both forest and savanna land. They came to this territory in the 18th

century, an area previously the home of Guro.

Statues were mostly

used for two purposes: the first was to incarnate a spirit of the bush,

asie usu or mbra; the second was to represent a spouse from the

other world, blolo bla or blolo bian.

According to

the Baule beliefs,

Asie usu (mbra) are extravagant

creatures that live in the bush and occasionally make contacts with human

beings. They are male and female, have colorful personalities, and often

have personal names. Therefore their figures are made in pairs. These

spirits are mischievous, but, if properly honored, will grant fruitful

harvests and hunts. They sometimes express desire, through the village

diviner, to be associated with a specific person. A figure is then sculpted

and worshipped in the house of the designated individual. This figure is

outstanding by its size and quality.

Material: wood

Size: 80" x 16" x 14" |

Male bush spirit figure or mbra.

Baule

statues were mostly used for two purposes: the first was to incarnate a

spirit of the bush, mbra or asie usu; the second was to

represent a spouse from the other world.

According to

the Baule beliefs,

mbra live in the bush and occasionally

make contacts with human beings. They are male and female, have colorful

personalities, and often have personal names. Therefore their figures are

made in pairs. Mbra is a Baule cult used for divination. Only certain

families have mbra, having acquired it in past generation. These

spirits are mischievous, but, if properly honored, will grant fruitful

harvests and hunts. They sometimes express desire, through the village

diviner, to be associated with a specific person. A figure is then sculpted

and worshipped in the house of the designated individual. This figure is

outstanding by its size and quality.

Material: wood

Size: 75" x 16" x 13" |

Mblo portrait mask. The Baule use three major

types of masks: a helmet in the shape of a buffalo head, masks related only

to the Goli festival and the masks representing a human face with

fairly realistic features. The masks of the last group are used in mblo

entertainment dances and are one of the oldest of Baule art forms. Such

a mask is usually a portrait of a particular known individual. Lustrous

curving surfaces, suggesting clean, healthy skin, are set off by delicately

textured zones representing coiffures, scarifications, and other ornaments.

The faces are idealized. Ornaments above the face have no iconographic

significance. These masks denote personal beauty, refinement, and a desire

to give pleasure to others. The greater importance of the portrait masks,

the need for the best dancers to wear them, and the requirement that the

portrait’s subject also be available and willing to dance made them more

rarely performed than animal masks, which could be worn by young, relatively

inexperienced dancers.

Material: wood

Size: 13" x 7" x 4" |

Double

mask with a female figure on top Double

mask with a female figure on top

Material: wood

Size: 34" x 6" x 4" |

22" x 8" x 7" |

Goli ram mask.

Baule society was characterized by extreme individualism, great

tolerance, a deep aversion toward rigid political structures, and a lack of

age classes, initiation, circumcision, priests, and secret societies.

The Baule are agriculturists; yams

are the staple, supplemented by fish and game; coffee and cocoa are major

cash crops. The Baule use three major types of masks: a

helmet in the shape of a buffalo head, masks related only to the Goli

festival and the masks representing a human face with rounded, fairly

realistic features. The present mask relates to the second type. According

to the Baule mythology, the ram is a heavenly demon or a spirit of

agriculture. These masks are used on the occasion of the new harvest, at the

visit of dignitaries, or at the funerals of notables.

Material: wood

Size: 25" x 16" x 8" |

may not be baule16" x 9" x 5"

may not be baule16" x 9" x 5" |

Mblo Mask

This

type of masks used in mblo dances is one of the oldest of Baule art

forms. These dances offer psychological relief in times of stress. The mask

is usually a portrait of a particular known individual. Lustrous curving

surfaces, suggesting clean, healthy skin, are set off by delicately textured

zones representing coiffures, scarifications, and other ornaments. The faces

are idealized.

Material: wood

Size: 49" x 9" x 7" |

Mankala (also called awele, wari or ma

kron) game. The game of mankala, though widespread, is

played more particularly in West Africa. It involves moving pawns on a board

with two rows of six holes. The goal is to capture the pawns in the opposite

row. The pawns can be made out of seeds, pebbles or pieces of metal. Many

ethnographical collections have mankala games, which are fine works

of art. This board is decorated with carved image of a crocodile. Two

parts. SOLD

Material: wood

Size: 49" x 9" x 7"

SOLD |

Weaver’s Pulley.

Weavers, always men, do not work in the courtyard but out in the public

place, often in an area where many weavers gather and every passerby greets

them. Their looms and weaving are watched and commented upon constantly.

Pulleys are made to be attractive and to make people talk about them and

their owner. Weavers said that a decorated pulley was simply for pleasure,

and that each sweep of the shuttle turned the pulley head from side to side,

as if it was shaking its head at the weaver.

Material: wood.

Size: 11" x 4" x 2"

|

Goli Elephant Mask

Côte d'Ivoire, have played a

central role in twentieth-century Ivorian history. They waged the longest

war of resistance to French colonization of any West African people, and

maintained their traditional objects and beliefs longer than many groups in

such constant contact with European administrators, traders, and

missionaries.

The Baule are agriculturists; yams are the

staple, supplemented by fish and game; coffee and cocoa are major cash

crops. They use three major types of masks: the helmet masks in the shape of

a buffalo head, the masks representing a human face with rounded, fairly

realistic features, and the third type including masks related to the

Goli festival. The masks of the last type and in

particular elephant masks are used during the Goli festivities held

to celebrate new crops, the visit of dignitaries or periods of mourning. The

masks appear in suite, with animal forms, both domestic and wild, preceding

human face masks.

Material: wood

Size: 21" x 8" x 5" |

Male bush spirit figure or mbra.

Baule

statues were mostly used for two purposes: the first was to incarnate a

spirit of the bush, mbra or asie usu; the second was to

represent a spouse from the other world.

According to

the Baule beliefs,

mbra live in the bush and occasionally

make contacts with human beings. They are male and female, have colorful

personalities, and often have personal names. Therefore their figures are

made in pairs. Mbra is a Baule cult used for divination. Only certain

families have mbra, having acquired it in past generation. These

spirits are mischievous, but, if properly honored, will grant fruitful

harvests and hunts. They sometimes express desire, through the village

diviner, to be associated with a specific person. A figure is then sculpted

and worshipped in the house of the designated individual. Male bush spirit figure or mbra.

Baule

statues were mostly used for two purposes: the first was to incarnate a

spirit of the bush, mbra or asie usu; the second was to

represent a spouse from the other world.

According to

the Baule beliefs,

mbra live in the bush and occasionally

make contacts with human beings. They are male and female, have colorful

personalities, and often have personal names. Therefore their figures are

made in pairs. Mbra is a Baule cult used for divination. Only certain

families have mbra, having acquired it in past generation. These

spirits are mischievous, but, if properly honored, will grant fruitful

harvests and hunts. They sometimes express desire, through the village

diviner, to be associated with a specific person. A figure is then sculpted

and worshipped in the house of the designated individual.

Material: wood

Size: 22" x 7" x 5"

|

19" x 4" x 4" |

Material: Wood

Size: 23" x 13" x 8" |

Materials: wood, fabric

Size: 18" x 4" x 4" |

Material: wood

Size: 15" x 5" x 4"

|

|

BENIN

Nigeria

The powerful ancient Benin kingdom was founded by the son of an

Ife king in the early 14th century AD. It was situated in the forest

area of southern Nigeria, 106 miles southeast of Ife. The art of bronze

casting was introduced around the year 1280. The kingdom reached its

maximum size and artistic splendor in the 15th and 16th century. For a

long time the Benin bronze sculptures were the only historical evidence

dating back several centuries into the West African past, and both the

level of technical accomplishment attained in bronze casting, as well as

the monumental vigor of the figures represented, were the object of

great admiration. Benin bronzes are better known than the artworks from

Ife or Owo due to their presence in Western museums since 1890s. In the

thirteenth century, the city of Benin was an agglomeration of farms

enclosed by walls and a ditch. Each clan was subject to the oba

(king). The “Benin style” is a court art from the palace of the oba,

and has nothing in common with tribal art. The Benin oba employed

a guild of artisans who all lived in the same district of the city.

Bronze figures ordered by the king were kept in the palace. The empire

flourished until 1897, when the palace was sacked by the English in

reprisal for an ambush that had cost the British vice-consul his life.

The numerous commemorative brass heads, free-standing figures

and groups, plaques in relief, bells and rattle-staffs, small expressive

masks and plaquettes worn on the belt as emblem of offices; chests in

the shape of palaces, animals, cult stands, jewelry, etc. cast by Benin

metalworkers were created for the royal palace. The heads were placed on

the altars of kings, of brass caster corporation chiefs and dignitaries.

Occasionally, a brass head was surmounted by a carved ivory tusk

engraved with a procession of different obas. The altar

functioned as a tribute to the deceased and a point of contact with his

spirit. Using the bells and rattle stuffs to call the ancestor’s spirit,

the oba offered sacrifices to him and to the earth on the altar.

The majority of figures represented court officials, equestrian figures,

queens, and roosters. Of objects in ivory: most elaborately decorated

human masks, animals, beakers, spoons, gongs, trumpets, arm ornaments,

and large elephant tusks covered with bands in figured relief. The

representations of these objects served above all to exalt the king, the

queen mother, the princes and royal household, army commanders, shown

with their arms and armor and their retainers (huntsmen, musicians), or

alternatively depicted important events.

When British forces entered Benin City in 1897 they were

surprised to find large quantities of cast brass objects. The

technological sophistication and overwhelming naturalism of these pieces

contradicted many 19th-century Western assumptions about

Africa in general and Benin – regarded as the home of ‘fetish’ and human

sacrifice – in particular. Explanations were swiftly generated to cover

the epistemological embarrassment. The objects must, it was supposed,

have been made by the Portuguese, the Ancient Egyptians, even the lost

tribe of Israel. Subsequent research has tended to stress the indigenous

origins of West African metallurgy. Yet it was the naturalism that

proved decisive. Their status was marked by the establishment of the

term ‘Benin bronzes’, despite their being largely of brass.

Following the bloody British punitive expedition to Nigeria,

about three thousand brass, ivory and wooden objects were consigned to

the Western world. At that time, western scholars and artists were

stunned by the quality and magnificence of these objects, more than

1,000 brass plaques were appropriated from the oba’s palace.

Dating from the 16th and 17th centuries, these

plaques were secreted in a storage room. It is thought that they were

nailed to palace walls and pillars as a form of decoration or as

references to protocol. They show the oba in full regalia along

with his nobility, warriors and Portuguese traders. The most elaborate

ones display a procession of up to nine people, while others depict only

fish or birds.

The majority of everyday Benin objects were made for and

associated with court ceremonies. The figures of a leopard were the sole

property of the oba – the leopard was the royal animal.

Pectorals, hip and waist ornaments in the shape of human or animal heads

were worn either by the oba or by major dignitaries. Brass staffs

and clippers surmounted by birds appeared during commemorating

ceremonies.

Despite the disappearance of the Benin kingdom, the Yoruba people living

on its territory continued to produce artwork inspired by the great

royal art of Benin. |

Benin style, Nigeria

Plaque with an oba.

When British forces entered Benin City in

1897 they were surprised to find large quantities of cast brass objects. The

technological sophistication and overwhelming naturalism of these pieces

contradicted many 19th-century Western assumptions about Africa

in general and Benin – regarded as the home of ‘fetish’ and human sacrifice

– in particular. The objects must, it was supposed, have been made by the

Portuguese, the Ancient Egyptians, even the lost tribe of Israel. Subsequent